A Brief History of the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research

The Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), which assures that safe and effective drugs are available to the American people, has gone through a functional and organizational metamorphosis since it began as a one-man operation to assess significant drug problems in the marketplace on the eve of the 1906 Pure Food and Drugs Act. In part, this change reflects the evolution of drug law and the chemotherapeutic revolution over the 20th century--and the concomitant changes in responsibilities of the Food and Drug Administration. But the change also reflects external and internal decisions on how best to provide safe and effective drugs to patients. Every branch of government, as well as other interests affected by FDA's policies, have had a role in the way this agency regulates drugs.

The following story summarizes some of the dynamics involved in the history of the drug regulatory function at FDA, especially with respect to the many organizational upheavals this function experienced over the past 90 years.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- 1.1 Creation of the Drug Laboratory in 1902

- 1.2 Early Drug Laboratory Work Under Dir. Lyman Kebler

- 1.3 1906 Act and the Drug Laboratory Becomes the Drug Division in 1908

- 1.4 The Four Laboratories of the Drug Division

- 1.5 False Therapeutic Claims and the Sherley Amendment

- 1.6 Work of the Drug Inspection Lab

- 2.1 Pharmacognosy Lab & Sherley Cases Unit

- 2.2 Offices of Drug Admin., Special Collab. Investigations

- 2.3 Div of Drugs to Office of Drug Control; George Hoover new Director

- 2.4 Collaborative Work of the Office of Drug Control

- 2.5 Investigations of Safety of Anesthetics; Lab of Drug Analysis

- 2.6 James Durrett, Office of Drug Control, and Organization by 1928

- 2.7 Marvin Thompson and Ergot Research in Pharmacology Lab

- 2.8 Frederick Cullen, Office Drug Control, and 1930s Studies of Dinitrophenol

- 2.9 Drug Div. Redux; Pharmacology Established as Independent Office for Drug and Food Work

- 3.1 1937 Elixir Sulfanilamide Disaster

- 3.2 1938 Act and Requirements for Premarket Drug Safety and New Labeling

- 3.3 Theodore Klumpp, Drug Division, and Chemical, Collaboration, Medical, & Veterinary Sections

- 3.4 New 1940s Authorities: Insulin and Antibiotic Certification and Prescriber Labeling Requirement; Antibiotic Testing Established in a New Office

- 3.5 Wartime Penicillin Testing; Robert Herwick Heads Drug Div; Sections & their Roles

- 3.6 From Drug Division to Bureau of Medicine; Chief Medical Officer; Stormont Heads Bur.

- 5.1 In-House Research Publications; Five Branches of the Bur.; Kessenich Arrives

- 5.2 Sen. Estes Kefauver Investigates Pharmaceutical Industry

- 5.3 Frances Kelsey, Thalidomide, and a Global Disaster Narrowly Averted Here

- 5.4 1962 Kefauver-Harris Drug Amendments

- 5.5 1962 Amendments & Clinical Trials; the First Advisory Committee

- 5.6 Post-1962 Reorganization of the Div of New Drugs

- 5.7 Reorganization of Scientific Functions in the 1960s; Antibiotics Returns to New Drugs

- 5.8 1960s Investigations of FDA and Drug Safety by Rep. Fountain

- 6.1 Drug Efficacy Study Implementation

- 6.2 Over-the-Counter Drug Review

- 6.3 Bur. of Medicine Reorganization Redux, with Five Divisions

- 6.4 First Outside Commissioner in Modern Times; Outside Help for Drug Work; Bur of Veterinary Medicine Splits Off

- 6.5 1969 Malek Report and Bur of Drugs and Other New Bureaus

- 7.1 National Center for Drug Analysis; Richard Crout heads Bur of Drugs; 7-Office Reorganization, 1974

- 7.2 Communicating Drug Information to Health Professionals

- 7.3 Sweeping Attempt at Drug Regulation Reform in 1970s Fails

- 7.4 Early Efforts to Mandate Patient Package Inserts

- 7.5 Provisioning Emergency Drugs at Three Mile Island; 1980s Reorganizations

- 8.1 The Merger of Drug and Biologics, 1982

- 8.2 Organization of the National Center of Drugs and Biologics

- 8.3 National Center for Drugs and Biologics Offices, mid-1980s

- 8.4 Orphan Drug Act and Federal Anti-Tampering Act

- 8.5 Regulating Direct-to-Consumer Prescription Drug Ads, 1980s

- 8.6 Generic Drugs and the 1984 Hatch-Waxman Act

- 8.7 Further 1980s Reorganization in the Drugs Office of NCDB

- 8.8 Changes in the Office of Compliance & the Office of Consumer and Professional Affairs

- 8.9 Accelerating Access to Investigational Drugs, Reporting Adverse Effects

- 9.1 NCDB Divided Back into Drugs and Biologics Centers, with Carl Peck, succeeded in 1994 by Janet Woodcock, the first Director of CDER

- 9.2 Initial Organization of CDER

- 9.3 Organization of Generic Drugs and the Generic Drug Crisis in the 1980s

- 9.4 Outside Evaluation of FDA and Ongoing Reorganization in CDER

- 9.5 1992 Prescription Drug User Fee Act and Its Impact on Drug Approvals and Review Times

- 9.6 Major Organizational Transformation of CDER in mid-1990s

- 9.7 CDER at the Dawn of the 21st Century

A BRIEF HISTORY OF CDER

Creation of the Drug Laboratory in 1902

(Harvey Wiley, the Chief Chemist of the Bureau of Chemistry)

During the 1902 annual meeting of the American Pharmaceutical Association, Harvey Wiley, the Chief Chemist of the Bureau of Chemistry, announced the formation of a Drug Laboratory within his organization. Wiley intended the Laboratory to assist with standardizing pharmaceuticals and unifying analytical results.

One of the nominees to lead this function was Lyman Frederic Kebler, the Chief Chemist at Smith Kline and French and a recognized expert in the detection of drug adulteration. Appointed Director of the Drug Laboratory in November 1902, he assumed the duties in March 1903.

Early Drug Laboratory Work Under Dir. Lyman Kebler

(One of the covers Collier's used in its campaign for the Pure Food and Drugs Act of 1906)

Initially, the Drug Laboratory worked on a variety of projects. One of the first was an investigation of the reagents used by the Bureau, which Kebler soon learned were not completely pure. The Laboratory spent much of its time in search of methods to improve pharmaceutical analyses. Kebler also alerted the public to problems with the drug supply in general.

1906 Act and the Drug Laboratory Becomes the Drug Division in 1908

(Carl Alsberg, Chief Chemist, Bureau of Chemistry)

Three years later, behind the long-time lobbying of Wiley, the Pure Food and Drugs Act became law; this prohibited interstate commerce of mislabeled and adulterated drugs and food. Wiley himself emphasized food-related issues as a greater health concern, but he gave some attention to patent medicines and prescription drugs; his successor, Carl Alsberg, elevated the importance of drug matters. By 1908 the Drug Laboratory underwent its first of what would be many major reorganizations. Renamed the Drug Division, it was divided into four laboratories: the Drug Inspection Laboratory, directed by George Hoover; the Synthetic Products Laboratory which W.O. Emery headed; the Essential Oils Laboratory, under E.K. Nelson; and the Pharmacological Laboratory, directed by William Salant. Kebler remained the Division Director.

The Four Laboratories of the Drug Division

(Drug Division, Essential Oils Laboratory)

The main focus of the Essential Oils Laboratory was the analysis of oils used therapeutically either alone or in combination with other chemicals, such as root-beer extract and oil of wintergreen. The Synthetic Products Laboratory was responsible for examinations of synthetic remedies, including the popular headache mixtures, and active ingredients in crude drug products.

(Radol was exposed as a hoax in 1908. The makers of this nostrum tried to cash in on people's fascination with radioactivity.)

The Pharmacological Laboratory investigated the physiological effects of drugs on animals. Most of their early efforts centered on caffeine, a subject of great interest to Wiley. Finally, the Drug Inspection Laboratory was the principal enforcement arm of the Division. For example, from 1909-1910 this Laboratory scrutinized over 900 domestic drug samples, around 1000 imported drugs, and recommended prosecution of 115 samples.

False Therapeutic Claims and the Sherley Amendment

(Representative Swagar Sherley was a Representative from Kentucky and Chairman of the House Committee on Appropriations.)

One of the first major challenges to drug regulation under the 1906 Act came in 1910. The Bureau had seized a large quantity of "Johnson's Mild Combination Treatment for Cancer," a worthless product that bore false therapeutic claims on its label. When the case came to trial, the judge determined that claims made for effectiveness were not within the scope of the Pure Food and Drugs Act, and ruled against the government. In 1912, Congress issued corrective legislation. The Sherley Amendment brought therapeutic claims within the jurisdiction of the Pure Food and Drugs Act, but required the Bureau to prove those claims to be false and fraudulent before they would be judged as illegal.

Work of the Drug Inspection Lab

(Bureau analysts received their samples from field inspectors such as John Earnshaw, pictured here in an extract packing plant in 1910.)

By this time, the scope of the Drug Inspection Laboratory's work had grown. For example, they investigated methodologies for the determination of morphine, nitroglycerin, and other drugs in combination preparations. Also, the Laboratory collaborated with the U.S. Pharmacopeia (USP) in a study of drug standards. The work of the Division of Drugs was not limited to domestic drug problems. They also studied imported drugs and chemicals and imported products of dubious therapeutic value. The Division also spent considerable time on an investigation of contaminated chloroform. Several manufacturers had been distributing chloroform in tin containers, which was prone to decompose into a substandard product compared to USP chloroform stored in glass.

Pharmacognosy Lab & Sherley Cases Unit

Though the 1906 Act led many patent medicines to abandon narcotics rather than label them, it was less successful in corralling exaggerated claims. In the mid-1910s, the Division of Drugs added two new components. The Pharmacognosy Laboratory was created in 1914. In addition to investigating crude drug products, this Laboratory studied improvements in crude drug processing to reduce waste. In 1916 the Division established a unit to investigate false and fraudulent labeling of drugs. This effort stemmed directly from the Sherley Amendment and was directed by M.W. Glover, a physician on detail from the U. S. Public Health Service (USPHS).

Offices of Drug Admin., Special Collab. Investigations

(Lyman Kebler in the laboratory, circa 1922)

The Bureau of Chemistry created the independent Office of Drug Administration in the early 1920s, headed by Glover, to assist the Division of Drugs with issues specific to drug labeling. In March 1923 Glover was recalled to the USPHS and the Office was abolished. At the same time, Kebler became head of the autonomous Office of Special Collaborative Investigations, which worked on mail fraud issues with the Post Office Department, and the Division of Drugs was reorganized.

Div of Drugs to Office of Drug Control; George Hoover new Director

(George Hoover (38) in a group shot, May, 1923)

In 1923, the Office of Drug Control replaced both the Office of Drug Administration and the Division of Drugs. Directed by George Hoover and organized in parallel with the new Office of Food Control, the Office was responsible for all work in the control of drugs, including crude drugs, manufactured drug ingredients, drug preparations, and patent medicines.

Collaborative Work of the Office of Drug Control

(Some of the official reference standards that the FDA's predecessors provided)

The Office continued to collaborate with outside concerns, including trade associations and the USP. The desire for increased manufacturing accuracy led to the formation of contact committees within the associations. After the committees completed studies on ways to improve accuracy, recommendations on implementation were published in the trade journals. In 1926 the Bureau's cooperation with the USP grew even greater through a program to provide standardized product samples of bioassayed drugs, such as digitalis, to be used as reference standards. This program continued until 1930.

Investigations of Safety of Anesthetics; Lab of Drug Analysis

(A pharmaceutical manufacturer's control room around the early 1940s)

After receiving reports of several deaths relating to impure anesthetics, the Office launched an investigation into the cause. There were several anesthetics on the market at the time, but this investigation focused on ether and ethylene. This was broadened over the years and continued into the mid-1930s. By the conclusion of the investigation, the Office determined that the decomposition of anesthetics was a result of poor manufacturing practices. As part of this inquiry, the Office established a Laboratory dedicated to drug analysis.

James Durrett, Office of Drug Control, and Organization by 1928

(James J. Durrett, M.D., Ph.G., Chief, Drug Control 1928-1931)

Beginning in 1928, the drug regulatory staff within the Food, Drug and Insecticide Administration (as the agency was known then) underwent several important personnel changes. George Hoover left the agency after directing the Office of Drug Control for five years and Lyman Kebler resigned as Director of Special Collaborative Investigations. As a result, Special Collaborative Investigations became a unit in the Office of Drug Control, which by this time also contained a Chemical Unit, a Medical Unit, a Veterinary Unit, and a Pharmacology Unit. The new Director of Drug Control was James J. Durrett, like Kebler a physician and pharmacist; Durrett was a professor of public health at the University of Tennessee at the time he joined FDIA.

Marvin Thompson and Ergot Research in Pharmacology Lab

(FDA's Pharmacological Laboratory)

A highlight in the Office's research was a study of ergot pharmacology conducted by Marvin R. Thompson. Initially, the Office had been concerned about decomposition of crude ergot; analysis had shown that this typically occurred during shipping. But the lack of knowledge of the pharmacology of ergot became obvious during this investigation. This led to the beginning of Thompson's work. In 1929 his paper was awarded the Ebert Prize of the American Pharmaceutical Association, bestowed annually for exceptional work in pharmacology. Thompson's paper was groundbreaking in many areas. He proposed modifications in the methods for assaying ergot, and showed that the USP standard for ergot could be improved by changing the preparation techniques.

Frederick Cullen, Office Drug Control, and 1930s Studies of Dinitrophenol

Shortcomings in the Pure Food and Drugs Act had been obvious since it became law. One weakness was the lack of authority to stop distribution of dangerous preparations claiming to reduce weight. In 1934 the Office of Drug Control, headed since 1931 by physician Frederick J. Cullen, began investigations on products containing dinitrophenol. This was a component in diet preparations that increased metabolic rate to dangerous levels, and it was responsible for many deaths and injuries. Since the law did not mandate drug safety, the Office of Drug Control could not seize the products, and was limited to posting warnings.

Drug Div. Redux; Pharmacology Established as Independent Office for Drug and Food Work

(FDA pharmacologist James C. Munch dictates results of an animal toxicity test)

In 1935 James J. Durrett returned to the Food and Drug Administration to direct the drug regulatory function, a function that once again was named the Drug Division. That same year the pharmacology responsibilities, theretofore part of the Division, became a separate, independent office, headed by Erwin E. Nelson. Nelson held the unique position of consultant to the agency while he remained on the faculty at Michigan from 1919-1937 and chair of the Pharmacology department of Tulane from 1937-1943. The main reason for the separation was to accommodate the increasing pharmacology needs of the food industry, especially in investigations of the effects of poisons and impurities in foods.

1937 Elixir Sulfanilamide Disaster

Continuing problems with dangerous drugs that fell outside the parameters of the Pure Food and Drugs Act finally received national attention with the Elixir Sulfanilamide disaster in 1937. Massengill distributed this preparation without testing for safety (which was not required by law). Because it contained diethylene glycol as a vehicle, a chemical analogue of antifreeze, over 100 people died, many of whom were children.

1938 Act and Requirements for Premarket Drug Safety and New Labeling

In June 1938 President Roosevelt signed the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act into law. Among other things, this law required new drugs to be tested for safety before marketing, the results of which would be submitted to FDA in a new drug application (NDA). The law also required that drugs have adequate labeling for safe use. All drug advertising was assigned to the Federal Trade Commission.

Theodore Klumpp, Drug Division, and Chemical, Collaboration, Medical, & Veterinary Sections

(Theodore Klumpp (standing) leads a meeting at FDA. He left FDA in 1941 for the American Medical Association and two years later became the president of Winthrop-Stearns.)

Three months after the President signed the 1938 Act, Theodore Klumpp, who received his medical training at Harvard and served on the faculty at Yale University, assumed leadership of the Drug Division after Durrett resigned. By this time, the Division consisted of a Chemical Section, a Collaboration Section, a Medical Section, and a Veterinary Section, and most of the work focused on reviewing NDAs. Within the first year of this requirement, the Division received over 1200 applications.

New 1940s Authorities: Insulin and Antibiotic Certification and Prescriber Labeling Requirement; Antibiotic Testing Established in a New Office

The early 1940s saw three major additions to FDA's responsibilities in the drugs area. The Insulin Amendment, passed in 1941, required all batches of insulin to be tested for purity, strength, quality, and identity before marketing. The testing was conducted by a unit in the Pharmacology Division. Also starting in 1941, the agency required prescriber labeling for all new drugs, in concert with the adequate directions for use provision of the 1938 Act. The Penicillin Amendment was passed in 1945, modeled on the Insulin Amendment. The former required batch certification of drugs wholly or partially composed of penicillin. Subsequent amendments extended the certification requirement to other antibiotics. Responsibility for the testing was placed in another separate and independent office, the Division of Penicillin Control and Immunology. Divided into four sections, Penicillin Certification, Immunology, Antiseptics, and Antibiotics, this Division's responsibility extended beyond testing of penicillin. In 1949 the Division was renamed the Division of Antibiotics to reflect the growing scope of functions and antibiotics.

Wartime Penicillin Testing; Robert Herwick Heads Drug Div; Sections & their Roles

In 1943 FDA began testing penicillin as part of the wartime development program. The first NDAs for this drug (some of which derived from the pictured strain of P. notatum) were approved in September of that year. The Drug Division at this time was under the leadership of a new director, Robert P. Herwick, who came to this position in 1941. He was trained in chemistry, pharmacology, toxicology, medicine, and law. Under Herwick's direction, the Division retained the same sections -- medical, chemical, and veterinary. The medical section was responsible for reviewing the safety and labeling of new drugs, and consulted on court cases. The veterinary section served the same function for animal drugs. The chemical section analyzed medicines and developed analytical methods for use by field chemists

From Drug Division to Bureau of Medicine; Chief Medical Officer; Stormont Heads Bur.

(Drug Inspectors Conference – 1946)

By 1945 the Division Director also served as the Chief Medical Officer of FDA, and soon thereafter the Drug Division was renamed the Division of Medicine. Herwick resigned in 1947 and was succeeded by Robert Stormont. Stormont was trained in pharmacology and medicine, and had served in the Naval Medical Corps before joining the FDA in 1946.

New Drug Section, Erwin Nelson, and Ralph Smith; 1951 Durham-Humphrey Amendment

Erwin E. Nelson (pictured on the left), the pharmacology consultant who directed the New Drug Section beginning in 1947, was promoted to Medical Director after Stormont's departure. Ralph Smith became the Chief of the New Drug Section after Nelson moved up, a position Smith held until the mid-1960s. Both an M.D. and Ph.D., Smith came to the FDA from the Tulane University School of Medicine, where he served as chairman of the Pharmacology Department. Under Smith's leadership, the agency approved over 7,000 New Drug Applications. Soon after the ascendancy of Nelson and Smith, Congress passed another law with a significant impact on drug regulation. The Durham-Humphrey Amendment of 1951 clarified the vague line between prescription and nonprescription drugs theretofore under the law. The Amendment specifically stated that dangerous drugs, defined by several parameters, could not be dispensed without a prescription, witnessed by the prescription legend: "Caution: Federal law prohibits dispensing without prescription."

Chloramphenicol and Adverse Event Reporting Program

The emergence of fatal blood dyscrasias associated with chloramphenicol in the early 1950s led to the search for better adverse reaction reporting. Drug regulation farther down in the distribution system came under scrutiny in 1955, when FDA undertook a pilot study of adverse drug reaction reporting. In cooperation with the American Society of Hospital Pharmacists, the American Medical Association, and others, the study focused on reactions reported by hospitals and pharmacists. Adverse reaction reporting at this time was voluntary and reports normally were scarce. This study blossomed into a more ambitious effort in 1957, a large-scale system for voluntary reporting to assist with post-marketing evaluation of new drugs. By 1963 the study had evolved into a voluntary reporting system with almost 200 participating hospitals.

The Sweeping 1955 Citizens Advisory Committee Report

The Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare formed the Citizens Advisory Committee in 1955 to review practices of the FDA and make recommendations to improve resource utilization. The 14-member Committee, consisting of leaders of industry as well as consumers, was chaired by G. Cullen Thomas of General Mills. Their report of June 1955 contained over 100 recommendations, including over two dozen regarding drugs specifically. Most of the drug recommendations dealt with the NDA program, especially suggestions for accelerating the review program. In general, the Committee recommended that the staff at FDA be increased at least threefold, and the budget as much as fourfold.

Interdicting Illegal Sales of Dangerous Drugs; Post-CAC Report Reorg; Holland Heads Bur.

The biggest drug enforcement problem at this time was the illegal distribution of barbiturates and amphetamines. FDA responded by training drug inspectors in undercover techniques (one such cadre is pictured). As a result of the recommendations of the 1955 Citizens Advisory Committee, the Division of Medicine underwent a major reorganization and became the Bureau of Medicine in 1957. By this time the Bureau was under Albert Holland, formerly of the New York University College of Medicine and Armour Laboratories, where he had been medical director. Holland had been appointed Medical Director in March 1954, following the resignation of Nelson in 1952.

In-House Research Publications; Five Branches of the Bur.; Kessenich Arrives

Included on these shelves of the Bureau of Chemistry around 1910 were the Bulletins and Circulars in which bureau scientists published much of their research.

In 1959 the Bureau began an internal publication, Bureau By-Lines, that fostered communication between the headquarters and field laboratories. Bureau By-Lines continued until 1982. At the end of the 1950s, the Bureau of Medicine consisted of five branches, the New Drug Branch, the Drug and Device Branch, the Veterinary Medicine Branch, the Medical Antibiotics Branch, and the Research and Reference Branch. The new medical director, William Kessenich, came to FDA in 1959 from the Department of Internal Medicine at Georgetown University.

Sen. Estes Kefauver Investigates Pharmaceutical Industry

(Drug plant inspector (right) checks the working drug formula against the master formula)

Strengthening the drug provisions of the 1938 Act were the focus of Senate hearings held beginning in 1959. These hearings, chaired by Senator Estes Kefauver of the Subcommittee on Antitrust and Monopoly of the Committee on the Judiciary, resulted in a bill introduced in 1961 that would require changes in drug patents, drug efficacy, greater oversight of drug studies, greater FDA access to company records, manufacturing controls, and other measures.

Frances Kelsey, Thalidomide, and a Global Disaster Narrowly Averted Here

(Kelsey receiving the award from President John F. Kennedy in 1962)

During the Kefauver hearings, FDA received an NDA for Kevadon, the brand of thalidomide that the William Merrell Company expected to market in the U.S., as it was already well established around the world. Despite ongoing pressure from the firm, medical officer Frances Kelsey refused to allow the NDA to become effective because of insufficient safety data. By late 1961 thalidomide's horrifying effects on newborns became known. Even though Kevadon was never approved for marketing, Merrell had distributed over two million tablets for investigational use, use which the law and regulations left mostly unchecked. Once thalidomide's deleterious effects became known, the agency moved quickly to recover the supply from physicians, pharmacists, and patients. For her efforts, Kelsey received the President's Distinguished Federal Civilian Service Award in 1962, the highest civilian honor available to government employees.

1962 Kefauver-Harris Drug Amendments

As a result of the narrowly avoided tragedy from thalidomide, Senator Estes Kefauver (5th from right above) re-introduced his bill. On October 10 President Kennedy signed the Drug Amendments of 1962, also known as the Kefauver-Harris Amendments. These Amendments required drug manufacturers to prove to the FDA that their products were both safe and effective prior to marketing. They also required that all antibiotics be certified, and gave FDA control over prescription drug advertising. With the new law, the review of antibiotic NDAs was transferred from the Division of New Drugs to the Division of Antibiotics. In May 1961, the designation "Division" replaced "Branch."

1962 Amendments & Clinical Trials; the First Advisory Committee

(Walter Modell)

The Drug Amendments also addressed the use of drugs in clinical trials, including a requirement of informed consent by subjects. FDA had to be provided with full details of the clinical investigations, including drug distribution, and the clinical studies had to be based on previous animal investigations to assure safety. FDA formed the first advisory committee, the Advisory Committee on Investigational New Drugs, for assistance in implementing the new law. The Committee, chaired by Walter Modell of Cornell University, served as a de facto interface between FDA and clinical investigators and other scientists around the country.

Post-1962 Reorganization of the Div of New Drugs

In the wake of the new law, the Division of New Drugs was restructured into five branches in 1962. The Investigational Drug Branch, directed by Kelsey, evaluated proposed clinical trials for compliance with investigational drug regulations. Earl Meyers, who began his career with FDA in 1939, was the director of the Controls Evaluation Branch, which reviewed the manufacturing controls proposed by drugs makers. The Medical Evaluation Branch assessed safety and efficacy data in NDAs. The New Drug Status Branch, under John Palmer, consulted with manufacturers about their NDAs and proposed dosing schedules for new products. The last branch, New Drug Surveillance, evaluated adverse reaction reports. Ralph Smith remained Division director, though he also served as acting Medical Director from the time Kessenich departed (1962) until March 1964, when Joseph Sadusk (pictured here) was appointed to that position. Sadusk chaired the Department of Preventive Medicine and Community Health at George Washington University before he joined FDA. Under Sadusk, the Bureau of Medicine consisted of four Divisions: Medical Review, directed by Howard Weinstein, New Drugs, directed by Smith, Research and Reference, under George Saiger, and Veterinary Medical, which was headed by Charles Durbin.

Reorganization of Scientific Functions in the 1960s; Antibiotics Returns to New Drugs

(Robert Roe (second from right, standing) and Daniel Banes (far right, standing) are pictured here at a 1961 joint conference between the FDA and the Food Law Institute)

Bureau of Scientific Standards and Evaluation and the Bureau of Scientific Research also had drug responsibilities. These Bureaus replaced the Bureau of Biological and Physical Sciences in 1964. The Bureau of Scientific Research was in charge of long-term scientific projects, under the direction of Daniel Banes; the Division of Pharmacology and the Division of Pharmaceutical Chemistry were located here. The Scientific Standards Bureau, led by Robert Roe, was responsible for decisions on certification and petitions; included in this Bureau was the Division of Antibiotics and Insulin Certification. In 1964 responsibility for antibiotics was shifted back to the Division of New Drugs in the Bureau of Medicine to centralize the review of NDAs for all types of human drugs.

1960s Investigations of FDA and Drug Safety by Rep. Fountain

(Rep. Fountain on a visit to Research Triangle Park, NC)

Uncertainty about the safety of America's drug supply continued after the passage of the Kefauver-Harris Amendments. As a result, Congress opened hearings in March 1964, chaired by Representative L.H. Fountain, to investigate FDA's efforts to promote drug safety. But Fountain's hearings took a comprehensive look at the agency's regulation of drugs, especially those that were removed from the market.

Drug Efficacy Study Implementation

(Among the products that came under intense scrutiny through DESI were preparations with multiple anti-infective ingredients, such as this one)

To further comply with the Drug Amendments of 1962 the FDA contracted in 1966 with the National Academy of Sciences/National Research Council to study drugs approved between 1938 and 1962 from the standpoint of efficacy. The Drug Efficacy Study Implementation (DESI) evaluated over 3000 separate products and over 16,000 therapeutic claims. The last NAS/NRC report was submitted in 1969, but the contract was extended through 1973 to cover ongoing issues. The initial agency review of the NAS/NRC reports by the task force was completed in November 1970. One of the early effects of the DESI study was the development of the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA). ANDAs were accepted for reviewed products that required changes in existing labeling to be in compliance. In September 1981 final regulatory action had been taken on 90% of all DESI products. By 1984, final action had been completed on 3,443 products; of these, 2,225 were found to be effective, 1,051 were found not effective, and 167 were pending.

Over-the-Counter Drug Review

(Over-the-counter (OTC) drugs).

In May 1972, FDA applied the principle of a retrospective review to over-the-counter (OTC) drugs. The structure for this OTC review would necessarily be different than that of the prescription drug review, mainly because of the vast array of available OTC products -- hundreds of thousands of different preparations. The OTC review focused on active ingredients, around 1,000 different items, and panels of experts were convened to evaluate these drugs. The agency would publish the results as a series of monographs in the Code of Federal Regulations, specifying the active ingredients, restrictions on formulations, and labeling by therapeutic category.

FDA formed 17 panels, consisting of seven voting members (medical, dental, and scientific experts) and non-voting representatives for industry and consumers. The panels were responsible for arranging the drugs into three categories: safe and effective, unsafe and/or ineffective (which should no longer be marketed), and probably safe and effective but needing further testing to establish significant proof. The review is ongoing. The agency eventually decided that drugs in the last category, like those in the second, would be taken off the market until sufficient proof dictated otherwise.

Bur. of Medicine Reorganization Redux, with Five Divisions

(A chemist in the Antibiotic Chemistry Branch uses a transparent "dry box" with built-in rubber gloves).

The Bureau of Medicine's interest in increasing efficiency for clearing new drugs and distributing work among staff members led to yet another restructuring in 1965. The new Bureau consisted of five Divisions and the Office of the Medical Director (still Sadusk). The five Divisions were New Drugs (Smith); Medical Review (Howard Weinstein); Medical Information, formerly the Division of Research and Reference (Donald Levitt); Veterinary Medicine (Charles Durbin); and Antibiotic Drugs (Raymond Barzilai). The Division of Antibiotic Drugs continued to evaluate antibiotic NDAs, but certification of antibiotics remained in the Bureau of Scientific Standards and Evaluation. The Medical Advisory Board also was established at this time to advise FDA on the problems faced by the industry, the medical community, and other health-related areas. Sadusk chaired the Board, and its members included leaders in medicine, pharmacology, dentistry, and veterinary medicine from across the country.

First Outside Commissioner in Modern Times; Outside Help for Drug Work; Bur of Veterinary Medicine Splits Off

(FDA Commissioner James Goddard swears in 65 physicians on 10 July 1966 for various assignments in the Bureau of Medicine including DESI, investigational drug and new drug review, and adverse reaction reporting.)

In 1966, the Bureau of Medicine introduced an Office and Division structure. The Office of New Drugs was responsible for reviewing all aspects of NDAs and investigational new drugs. The Office of Drug Surveillance reviewed adverse drug reaction reports and supplemental drug applications. Finally, the Office of Medical Review was responsible for regulatory actions. This latest reorganization also reflected the establishment of the Bureau of Veterinary Medicine in November 1965. Directed by M. Robert Clarkson, the Bureau was responsible for review of both veterinary drugs and devices. The human device program remained in the Bureau of Medicine until 1971. Sadusk resigned after overseeing the reorganization. Herbert Ley, who had been at both Harvard Medical School and George Washington University, succeeded Sadusk in September 1966. In 1967 the Bureau of Medicine replaced the Office of Drug Surveillance with the Office of Marketed Drugs, which was responsible for approval of supplemental applications. In addition, the Bureau established the Office of Medical Support to centralize a variety of functions in the Bureau, such as medical advertising and adverse reaction reporting.

1969 Malek Report and Bur of Drugs and Other New Bureaus

(An inspector checks ampules for extraneous matter on a plant's inspection line.)

In 1969 FDA proposed the first major GMP revisions since 1963. In December 1969, a Departmental study known as the Malek Report recommended a major reorganization of FDA along products lines. Indeed, the Bureaus of Compliance, Medicine, and Science soon were replaced by the Bureau of Drugs and the Bureau of Foods, Pesticides and Product Safety. To form the Bureau of Drugs, the drug and device activities of the Bureau of Medicine were combined with the pharmaceutical science responsibilities of the Bureau of Science and the drug and device compliance activities from the Associate Commissioner for Science. The new Bureau of Drugs consisted of four Offices: New Drugs, Marketed Drugs, Compliance, and Pharmaceutical Sciences.

National Center for Drug Analysis; Richard Crout heads Bur of Drugs; 7-Office Reorganization, 1974

(Summary of early work at the National Center for Drug Analysis).

The National Center for Drug Analysis (NCDA) opened in St. Louis, Missouri, in July 1967 to conduct large scale tests of drug products. Prior to this, NCDA was part of the Division of Pharmaceutical Sciences in the Bureau of Science (formed in 1966 after the Bureau of Scientific Standards and Evaluation merged with the Bureau of Scientific Research). In its first year, the NCDA examined over 7,000 samples. From 1973 until 1981, the Bureau was under the direction of J. Richard Crout. Crout, a pharmacologist at Michigan State, came to the attention of Henry Simmons (1970-1973), Crout's predecessor, while serving on the Ad Hoc Science Advisory Committee (Ritts Committee). The latter investigated the place of science within FDA. Following a 1973 management study of the overall drug function, the Bureau of Drugs reorganized in November 1974 into seven offices: Planning and Evaluation, Compliance, Information Systems, Biometrics and Epidemiology, Pharmaceutical Research and Testing, Drug Monographs, and New Drug Evaluation.

Communicating Drug Information to Health Professionals

During the early 1970s, the FDA started two new forums to increase drug communication with the public. The Bureau of Drugs launched the FDA Drug Bulletin in 1971. The Bulletin alerted physicians and pharmacists to changes in drug use and labeling requirements. The National Drug Experience Reporting System also began in 1971. The NAS had been studying the problem of not only how to catalogue and store information about adverse drug reactions, drug abuse, and drug interactions, but also how that information could be made available to health professionals. The study concluded that since FDA had already collected the data, they should take the lead on creating and maintaining the system.

Sweeping Attempt at Drug Regulation Reform in 1970s Fails

(HEW Secretary Joseph A. Califano).

A renewed push for changes in drug regulation began at the highest level of the Department. HEW Secretary Joseph Califano felt that, for such changes to be effective, they had to be made through legislation rather than administrative policy. The initial bill, introduced in Congress on March 17, 1978, was titled the Drug Regulation Reform Act.

It contained nine main provisions: to increase consumer protection, encourage drug innovation, increase consumer information, protect patient rights, improve FDA enforcement, promote competition and cost savings through generic drugs, increase FDA's public accountability, make additional drugs available, and encourage research and training. The effort during 1978 was unsuccessful, but the bill was reintroduced the following year. The Senate approved the bill in September 1979, but the House did not take action and the measure died.

Early Efforts to Mandate Patient Package Inserts

However, efforts to promote one of the provisions in the Senate-approved version of the Drug Regulation Reform Act, the requirement for drug manufacturers to provide package inserts for all prescription products, continued after the reform bill. Since 1970 the FDA had required the inserts only for isoproterenol inhalers and oral contraceptives. In July 1979 FDA proposed a program to provide patients with additional information about their prescription drugs, including a description of the drug's uses, risks, and side effects. Under the proposal, the manufacturer would print the information and the provider (pharmacist, doctor, nurse, etc.) would give the insert to the patient. But by September 1980, under the weight of well-organized opposition to the program, FDA dropped the insert project.

Provisioning Emergency Drugs at Three Mile Island; 1980s Reorganizations

In March 1979 FDA suspended both labeling and manufacturing requirements for emergency production of potassium iodide, intended for those in the vicinity of the Three Mile Island nuclear emergency. During the early 1980s the Bureau of Drugs underwent several substantial organizational changes, ranging from discrete changes in branch substructures to a revamping of the entire organization. Among the less ambitious alterations, the Bureau restructured the Division of Drug Information Resources in the fall of 1980, and the Prescription Drug Labeling Staff was transferred from the Office of the Division Director to the Division of Drug Advertising the following year. In March 1982 several Divisions changed names (and, to varying extents, responsibilities): the Division of Product Quality became the Division of Drug Quality Evaluation, the Division of Drug Manufacturing changed to the Division of Drug Quality Compliance, and the Division of Drug Advertising became the Division of Drug Advertising and Labeling.

The Merger of Drug and Biologics, 1982

The biggest organizational change during this time was the merger of the Bureau of Drugs and the Bureau of Biologics to form the National Center for Drugs and Biologics (NCDB) mandated in 1982 and effected the following year. The new Director of the NCDB, Harry Meyer, Jr., had been head of the Bureau of Biologics. Biologics control originated in 1902 in the Hygienic Laboratory, precursor of the National Institutes of Health; in 1972 this responsibility was transferred to FDA. The purpose of this reorganization was to streamline FDA's approval procedures in drugs and biologics and to increase the public's assurance of the safety and effectiveness of the drug supply.

Organization of the National Center of Drugs and Biologics

The NCDB consisted of five offices: New Drug Evaluation, Drugs, Biologics, Management, and Scientific Advisors and Consultants. The Office of New Drug Evaluation, directed by Robert Temple, was formed from the six Divisions in the Bureau of Drugs that reviewed NDAs. Jerome Halperin was the first Director of the Office of Drugs, which included the remaining Divisions from the Bureau of Drugs that conducted research and developed standards for the safety and effectiveness of drugs. The Office of Biologics, under John Petricciani, managed the Divisions from the Bureau of Biologics. Administrative functions were in the Office of Management, which Russell Abbott headed. The establishment of the Office of Scientific Advisors and Consultants, directed by Morris Schaeffer, facilitated scientific proficiency and research in drugs and biologics. Finally, the reorganization abolished the National Center for Antibiotics Analysis. Formed in 1968 from the old Division of Antibiotics and Insulin, the Center had been responsible for certification and testing of antibiotics. In 1981 the FDA proposed to phase out the certification program by late 1982, and the program ended on October 1, 1982.

National Center for Drugs and Biologics Offices, mid-1980s

(Commissioner Frank Young, appointed in 1984, faced the wrath of AIDS activists in search of both more therapeutic options and a greater voice in the formation of policies affecting AIDS patients.)

In 1984 all of the National Centers within FDA were redesignated simply as centers. At this time, the Center for Drugs and Biologics established or reengineered five offices. The Office of Compliance, directed by Daniel Michels, was made up of the Divisions of Drug Labeling Compliance, Drug Quality Compliance, Drug Quality Evaluation, Scientific Investigations, Biological Product Compliance, and Regulatory Affairs. The Office of Management, still under Abbott, was comprised of the Divisions of Planning and Evaluation, Administrative Management, and Drug Information Resources.

Temple became Director of the Office of Drug Research and Review and led the Divisions of Cardio-Renal Drug Products, Neuropharmacological Drug Products, Oncology and Radiopharmaceutical Drug Products, Surgical-Dental Drug Products, Drug Biology, Drug Chemistry, and Drug Analysis. Peter Rheinstein headed the Office of Drug Standards, which consisted of the Divisions of OTC Drug Evaluation, Biopharmaceutics, Generic Drugs, and Drug Advertising and Labeling. The Office of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, under Gerald Faich, was made up of the Division of Biometrics and the Division of Drug Experience. Finally, Elaine Esber led the Office of Biologics Research and Review.

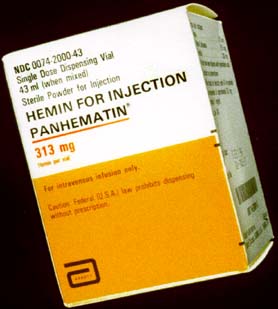

Orphan Drug Act and Federal Anti-Tampering Act

(Hemin was one of the first two orphan drugs recognized under the 1983 Act.)

Drug responsibilities increased in several ways in the mid-1980s. The Orphan Drug Act of 1983 employed several means to promote development of products for rare diseases. Among the provisions of this law, the sponsors of drug candidates could petition the agency for assistance in planning animal and clinical protocols. Also, the sponsor was allowed seven years of marketing protection, and the law provided a 50 percent tax credit for investigation expenses. As a result of this Act, in early 1983 an Orphan Product Development office was established in the Office of the Commissioner, under Marion Finkel. Also in 1983, Congress passed the Federal Anti-Tampering Act in the wake of the Tylenol poisonings. This law amended the U.S. Code to provide penalties for tampering with or threatening to tamper with any product covered by the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act.

Regulating Direct-to-Consumer Prescription Drug Ads, 1980s

Advertising in professional journals was a well-accepted practice, where doctors, pharmacists, and other health professionals could read information on side effects and other disclosure data adjacent to the promotional information. Direct to consumer television advertising of prescription drugs emerged in May 1983. Boots Pharmaceuticals was the first manufacturer to use this new venue in promoting its Rufen brand of ibuprofen. FDA took action against the advertisement out of concern that consumers would not be able to read the long list of side effects that flashed quickly across the screen. The commercial was replaced with an acceptable version.

Generic Drugs and the 1984 Hatch-Waxman Act

The Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984 expedited FDA review of generic versions of brand name drugs without repeating efficacy and safety data. The first Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) approved under this law was for generic disopyramide, marketed as Norpace and used in the treatment of cardiac arrhythmias. As a result of this legislation, several Divisions in the Office of Drug Standards added branches to assist with the review of ANDAs. The law also provided manufacturers with the opportunity to apply for an extra five years of patent protection to make up for time lost during the FDA approval process.

Further 1980s Reorganization in the Drugs Office of NCDB

Several important organizational changes emerged during this period. In 1985, the Drugs and Biologics Fraud Branch was established within the Division of Drug Labeling Compliance to combat health fraud in the drug and biologic areas. That same year, the Division of Drug Chemistry was abolished and its staff reassigned to the Division of Drug Analysis for NDA review. Also, the Division of Drug and Biologic Product Experience was renamed the Division of Epidemiology and Surveillance

Changes in the Office of Compliance & the Office of Consumer and Professional Affairs

(Charles Roberts of the Center for Drugs and Biologics examines an AIDS testing kit, which FDA approved in 1985.)

The structure of the Office of Compliance changed in 1986, resulting in five Divisions: Drug Labeling Compliance, Drug Quality Evaluation, Scientific Investigations, Regulatory Affairs, and Manufacturing and Product Quality. The Office of Consumer and Professional Affairs, formed after the merger of the Bureau of Drugs and the Bureau of Biologics, was abolished in 1987. Also in 1987, Paul Parkman became the Director of the Center for Drugs and Biologics, and Gerald Meyer became his deputy.

Accelerating Access to Investigational Drugs, Reporting Adverse Effects

The 1980s witnessed increasing concern for drug regulation by patient advocacy groups, exemplified here by a 1988 protest at the Parklawn Building in Rockville by the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power. Additional laws and policies of the 1980s had an impact on drug approval and distribution. For example, the agency strengthened reporting requirements for adverse reactions in 1985. The new requirements addressed all prescription drugs, including older pharmaceuticals that predated FDA approval. New regulations for investigational drug development also went into effect in 1985. The new rules increased the availability of experimental drugs, including compassionate use of drugs under research for patients with serious and/or life-threatening conditions. In 1988 FDA promulgated treatment IND regulations. These allowed desperately ill patients to receive promising new drugs before full approval had been completed. Congress passed the Prescription Drug Marketing Act in the same year. This law prohibited the purchase, sale, trade, and -- with exceptions -- reimportation of drug samples. It also required drug wholesalers to register with states.

NCDB Divided Back into Drugs and Biologics Centers

(Carl Peck, succeeded in 1994 by Janet Woodcock, the first Director of CDER)

On October 6, 1987, the Center for Drugs and Biologics was split into the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research and the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER). This split was necessary because of the increasing volume of NDAs, to provide proper high-level attention to the growing problem of AIDS, and to address other issues in drug and biologic evaluation. Carl Peck became the first Director of CDER, and Parkman was named Director of CBER. Peck, who had been Director of the Department of Clinical Pharmacology at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences when he came to FDA, continued as Director until 1994, when Janet Woodcock became the second Director of CDER. Woodcock, whose background is in internal medicine and rheumatology, had been in CBER before assuming her position in the Center for Drugs.

Initial Organization of CDER

(In the Spring of 1988 the Public Health Service sent this pamphlet to over 100 million households in the U.S.)

When CDER began it consisted of six offices: Management (directed by Robert Bell), Compliance (Michels), Drug Standards (Rheinstein), Drug Evaluation I (Temple), Drug Evaluation II (James Bilstad), Epidemiology and Biostatistics (Faich), and Research Resources (Jerome Skelly). The Division of Antiviral Products was established in 1988 within the Office of Drug Evaluation II to assist with review of drugs for AIDS and other indications. The Office of the Center Director added two new staff offices in 1989. The Professional Development Staff developed and coordinated programs to assist with recruiting and training of Center staff, and the Pilot Drug Evaluation Staff fostered new ideas to streamline the drug approval process.

Organization of Generic Drugs and the Generic Drug Crisis in the 1980s

Also at this time, CDER established the Office of Generic Drugs to assume responsibility for review of ANDAs, which had been located in the Office of Drug Standards. In addition, the Generic Drugs Advisory Committee was formed to assist the Office of Generic Drugs with approval issues. This Committee advised the Office on scientific and technical matters related to the safety and effectiveness of generic drugs. In the wake of the convictions of five FDA reviewers for unlawful contacts with regulated industry, Congress passed the Generic Drug Enforcement Act in 1992. This law provided a variety of penalties for illegal acts involved with ANDA approvals.

Outside Evaluation of FDA and Ongoing Reorganization in CDER

In March 1990 HHS Secretary Louis Sullivan appointed a committee, headed by former FDA Commissioner Charles Edwards, to review the agency's mission, structure, priorities, staffing, and budget. One committee member resigned when he was selected by President Bush as the Commissioner-designate: David Kessler.

Reorganizations in response to scientific and legislative mandates continued in the 1990s. For example, the Office of Research Resources created the Division of Clinical Pharmacology. This Division, consisting of the Chemotherapy and Analytical Methodology Branch and the Preclinical Development Branch, studied clinical pharmacology and expanded CDER's interests in clinical investigations.

1992 Prescription Drug User Fee Act and Its Impact on Drug Approvals and Review Times

The Prescription Drug User Fee Act, passed in 1992, required drug and biologic manufacturers to pay fees to the FDA for the evaluation of NDAs and supplements. Also, the firms would pay an annual establishment fee and product fees. Congress required FDA to apply user fees to hire more reviewers, and thus expedite the reviews. Following the passage of this legislation, the number of new drug approvals has indeed increased steadily each year, from 63 in 1991 to a record 131 in 1996. Also, median approval times for new molecular entities and for all NDAs have been cut in half from 1993 to 1998 from about two years to twelve months for both categories.

Major Organizational Transformation of CDER in mid-1990s

Advisory committees have been an important element in drug review since the 1960s. Pictured here is a meeting of the Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee. Recently CDER underwent a Center-wide reorganization, beginning in 1995. Within the Office of Drug Evaluation I (ODE I) the Division of Oncology and Pulmonary Drug Products was split into separate Divisions; the Division of Oncology Drug Products stayed in ODE I and the Division of Pulmonary Drug Products moved into ODE II. Also, nine new Offices were established and the functions of one were moved. Included in the new Offices were three additional Offices of Drug Evaluation, an Office of Training and Communication, the Office of Review Management, the Office of Pharmaceutical Science, the Office of New Drug Chemistry, the Office of Clinical Pharmacology and Biopharmaceutics, and the Office of Testing and Research. The functions of the Office of Over-the-Counter Drug Evaluation were transferred to ODE V.

CDER at the Dawn of the 21st Century

Through the years, responsibilities within FDA for drug regulation have undergone major changes. Most of these came as a result of innovations in drug development and additions to legislative authority. When Lyman Kebler was hired in 1902, he was basically a one-man bureau who had corrupt reagents and half a desk to fight the most egregious offenses of a largely unregulated industry. As of 1994, CDER was the largest headquarters component of FDA, consisting of almost 1500 men and women working in several buildings. The complexity and challenges of drug review are multiplying as the sophistication of drug design and manufacturing increases, which speaks to the importance of maintaining a well-trained and adequately supported group of agency drug officials, for the good of the public health.