OII Investigators Help Keep Food and Water Safe—at 35,000 Feet

On a steamy 86-degree day last July at Muhammad Ali International Airport in Louisville, KY, Alan Escalona, an investigator with the FDA, crouched on the tarmac scribbling in a notebook. He looked over to a silver tank hooked up to a Boeing 737 aircraft parked next to him and proceeded to examine its inner plumbing with a flashlight.

Escalona, who works for FDA’s field force, the Office of Inspections and Investigations, was focused on passenger safety that day. But not in the way you might think.

His concern: that the next round of travelers to board the plane wouldn’t get sick from the water, ice, or food they might be served.

Careful Standards, Verified in Person

We don’t give much thought to the safety of our food and water when we fly. For this we can thank public health regulations set by the FDA, Federal Aviation Administration, and Environmental Protection Agency, which are then to be followed by industry.

We can also thank those working behind the scenes—on-the-ground and on-board planes as needed—investigators, like Escalona, who see to it that airline staff are following all federally required sanitation steps, so that aircraft drinking water, snacks, and meals aren’t compromised by bacteria, harmful chemicals, or any other contaminants.

Escalona specializes in food and nutritional supplement inspections, while other of his colleagues, based out of OII field offices spread across the country, are trained to inspect facilities making drugs and medical products. For food-focused investigators, with OII’s Food Products Inspectorate, this means being dispatched regularly to places where our food comes from—any of the thousands of farms and food processing and manufacturing facilities in this country, as well as passenger aircraft, too.

Following the Water

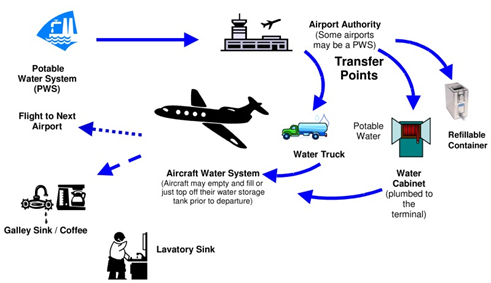

Airplanes must refuel. They must also maintain a potable water supply, including the water that’s used to brew the coffee and tea we drink onboard a flight. The environment in which this water is accessed, moved across a tarmac, and then piped into an actual aircraft can be extensive and complex. Water trucks, containers, and cabinets, along with numerous hoses and tubes, all come into play.

As any public health investigator with OII knows, this complex ecosystem of moving water, where contact points on hoses and other surfaces abound, presents countless opportunities for illness-causing bacteria and germs to pose risks to passengers.

“That why it’s important,” explains Escalona, “for airline staff and crew to follow good food and water handling safety practices. This includes things like wearing the appropriate personal protective equipment when handling lavatory equipment.”

Storage Rooms and Sanitation

In addition to inspecting water delivery components on the tarmac and inside the plane, Escalona also assesses snack, condiment, and ice storage spaces maintained by airlines at the airport. On the day he was in Louisville, he also spent time observing behaviors, including how employees handled the ice scoop that was used to bag ice being carried out to the plane.

A colleague of Escalona’s had inspected the airline previously and cautioned staff about not adequately sanitizing the metal scoop. They hadn’t used disposable gloves either. Escalona followed up to be sure that required best practices were in use. He also had specific questions for personnel: about the airline’s water filtering services, how often the snack/condiment room was cleaned, where staff handwashing occurred (versus utensil sanitation), among others.

But he was soon back to his in-depth sensory work again, even crawling behind food and ice cabinets as needed, hunting for stains, dirt, debris, signs of insect or rodent pests—any indication that bacterial or mold growth or other insanitary conditions existed.

Sharing Findings, Building Food Safety Culture

No “egregious” findings were made that day in Louisville. But had Escalona discovered any serious risks to public health, he would have likely recommended immediate regulatory action, including a possible pause in operations.

Even still, the investigator walked airline staff through all the observations he’d jotted down in his notebook. He took plenty of time to answer their questions, particularly to explain the real risks of transmitting foodborne and waterborne illness when food and water handlers, for instance, don’t take those extra seconds to use sanitizer or put on gloves.

“As investigators, we can’t be everywhere,” explains Escalona. “There are just too many food facilities in this country.”

“But what we can do, in addition to conducting thorough, science-driven inspections that hold industry accountable, is to help build good food safety practices among all those we meet in the field.”