80 Years of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act

In the early 20th century, Americans were inundated with ineffective and dangerous drugs, and adulterated and deceptively packaged foods. Compounding the problem, consumers had no way of knowing what was actually in the products they bought. The passage of the 1906 Pure Food and Drugs Act marked a monumental shift in the use of government powers to enhance consumer protection by requiring that foods and drugs bear truthful labeling statements and meet certain standards for purity and strength. While the 1906 law laid the cornerstone for the modern FDA, as time went on it became clear that it had major shortcomings, which limited the agency's ability to protect consumers. The law offered no way to remove inherently dangerous drugs from the market and set such a high burden of proof for misbranding, i.e., intent to defraud, that the agency was rarely able to take action against a company for fraudulent products. In addition, the law provided no authority over cosmetics, medical devices, or advertising, and imposed no standards for foods.

To help make the public aware of the 1906 law’s limitations, the FDA’s Chief Education Officer, Ruth deForest Lamb, and Chief Inspector, George Larrick, created an influential traveling exhibit in 1933 to highlight about 100 dangerous, deceptive, or worthless products that the FDA lacked authority to remove from the market. The exhibition was so shocking it was dubbed the "American Chamber of Horrors" by a reporter who accompanied First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt to view the exhibit. The name stuck. Lamb also adapted the exhibit into a 1936 book in which she explained that "All of these tragedies … have happened, not because Government officials are incompetent or callous, but because they have no real power to prevent them."

The Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act

This year marks the eightieth anniversary of President Roosevelt’s signing of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA), which closed many of the legal loopholes highlighted in the American Chamber of Horrors and forever altered the landscape of consumer protection in America. For the first time, the FDA had authority to regulate medical devices and cosmetics, and to establish standards for foods. Drugs and devices were required to provide adequate directions for use; falsely labeled uses were misbranded; and there was no longer a need to establish intent to defraud to prove misbranding. In addition, it became illegal to market drugs or devices that inherently endangered health, and all new drugs had to be proven safe for their labeled use before they could be marketed. Today, this important law still looms large in guiding the FDA’s mission.

Chamber of Horrors Photo Gallery

To download pictures of these and other products included in the historic Chamber of Horrors exhibit, visit the American Chamber of Horrors album ![]() on FDA’s Flickr photostream.

on FDA’s Flickr photostream.

Banbar

Banbar, a worthless concoction that claimed to treat diabetes, was offered as an alternative to the only useful drug for that disease, insulin. FDA provided evidence in court of Banbar’s lack of effect and disproved the manufacturer’s evidence of its value in the disease. But the government still lost this case, having failed to show the manufacturer intended to defraud the consumer.

Bowman’s Abortion Remedy

Bowman’s Abortion Remedy promised to treat Contagious Abortion (aka, brucellosis) in cattle. This highly contagious disease impedes breeding and milk production. Before an effective vaccine was developed, the only means of preventing its spread in a herd was to segregate or euthanize infected animals. If a desperate farmer used a worthless product like Bowman’s, it allowed the disease to languish untreated and infect more animals. When FDA won a seizure action against Bowman’s, the manufacturer simply moved its therapeutic claims from the label to its advertising.

Bred-Spred

Bred-Spred was a line of “jellies” in beautiful colors and many flavors, packaged in glass jars. But, it was not a traditional jam or jelly, as defined by the industry standard of 50% fruit/juice. Instead, it had no fruit or juice at all. Just artificial colors, artificial flavors, pectin, with a few hayseeds thrown in to simulate strawberry seeds. Many state governments and the federal government worked in concert to get the product off of the market because it, and products like it, threatened the entire jam and jelly industry.

Crazy Water Crystals

Crazy Water Crystals, advertised widely on the radio, allegedly derived from health-giving Crazy Mineral Water found in Texas. FDA seized the latter multiple times in the 1910s and 1920s for adulteration and misbranding, in part for claims to treat Bright’s disease, rheumatism, liver disorders, etc. The Crystals emerged by the early 1930s, but without the labeled therapeutic claims, which were transferred to ads.

Dinitrophenol

Based on preliminary results that the industrial chemical, dinitrophenol, could rapidly accelerate the metabolism and produce weight loss, many preparations became widely available in the early 1930s. Even though dinitrophenol caused fatal blood disorders, cataracts, and other serious side effects, it was considered a cosmetic rather than a drug, and thus beyond the reach of the law.

Dr. Hess’s Poultry Tablets and Lee’s Gizzard Capsules

Dr. Hess’s Poultry Tablets and Lee’s Gizzard Capsules were among the many “vermifuge” treatments for chicken worms popular in the early 20th century. The products promised to cure hens of all intestinal worms – even though there were only effective remedies for roundworms available at the time. Because these fraudulent products often contained nicotine and kamala they could disrupt egg production cycles for several months.

Egg Noodles

Egg Noodles have slightly more nutritive value than other marketed dried pastas and were slightly more expensive. An enterprising manufacturer tried to convince consumers that his pasta was actually egg noodles by packaging them in yellow cellophane to give them a yellow tinge that would have let a consumer distinguish between egg noodles and pasta.

Flavoring Extracts

Flavoring extracts were among the more expensive items in the grocery store. Consumers would be used to buying them in standard bottles and this would appear to be one that held 2 oz. of liquid. But with the label removed, it was clear that the sides were thickened so that the bottle only held a single oz. of fluid extract, making it one of the most egregious food packaging frauds.

Jad Salts

Jad Salts, which combined several chemicals into a purge and diuretic, was seized by FDA in the early 1920s for claims to cure rheumatism, dizziness, joint pains, and other problems. However, Jad’s maker joined the ranks of “reducing racketeers” by the early 1930s when Jad was relabeled to treat obesity, yet another spurious if not unsafe product beyond the reach of the law.

Koremlu

Koremlu was presented as a revolutionary breakthrough in eliminating unwanted body hair when it hit the market in the Spring of 1930. Within a year over 120,000 jars were sold! Its depilatory agent was thallium acetate – a common rodenticide that can cause neuromuscular damage, respiratory problems, blindness and permanent hairloss. One 26-year-old woman reportedly lost her teeth, eyesight, ability to walk and her job due to Koremlu.

Lash Lure

Lash Lure was an aniline (coal tar-based) eyelash and eye brow dye that promised consumers more lasting beauty effects than mascara or eyebrow pencil. However, in reality, the toxic dye was highly irritating and caused eyebrow and eyelash loss, as well as vision impairment and even blindness. Like many cosmetics of the time, it was not tested for safety and did not disclose ingredients, so consumers had no way of knowing the real danger it posed to their health.

Lead Trinkets and Coins

During the Depression, lead “trinkets” and coins were embedded in children’s candies. Dr. Chevalier Jackson, a pioneer in the field of laryngology, identified the growing number of choking deaths among children and launched an awareness campaign. Such additions were ruled legal under the law.

Lydia Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound

Lydia Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound was one of the most famous of the female tonics in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. FDA took action against false claims on the label of the product in 1915, but the company just revived them for radio listeners. The Pinkham proprietors were one of the companies that fought hardest against giving FDA the authority to regulate advertising in the new law.

Marmola

Marmola was an obesity treatment introduced in 1907, and like many it relied on dried thyroid. Heavily advertised, including on the radio, consumers never heard that it could produce classic symptoms of hyperthyroidism, including rapid heart rate and insomnia. However, since obesity at this time was considered more a cosmetic than a medical problem, Marmola remained on the market.

Nuxated Iron

Nuxated Iron, the brainchild of E. Virgil Neal, a former hypnotist with a conviction for mail fraud and a profitable French cosmetics company, promised to invigorate, rejuvenate, and enhance athletic performance. Neal used cutting-edge marketing tactics, including paid celebrity testimonials to hawks these tablets, which consisted of iron and nux vomica, a derivative of the potentially lethal strychnine plant. At least one young boy died from consuming nearly an entire bottle of Nuxated Iron.

Othine

Othine promised to remove brown spots and lighten skin, to help women achieve the pale, flawless skin that was upheld as a beauty standard in the 1930s. Yet, to produce these results, Othine relied on the active ingredient mercury, whose toxic properties were well-known by that time. In their quest for beauty, consumers unwittingly risked bone deterioration, tooth loss, neurological, pulmonary and renal damage, as well as cognitive and sensory impairment, and even death.

Pabst’s Okay Specific

Pabst’s Okay Specific, a 60 proof elixir, boldly proclaimed to “cure positively and without fail… when all other medications have failed” gonorrhea and gleet discharge. Pabst’s promotional materials, such as this matchbox cover, coyly skirted social taboos about sexually transmitted diseases that likely increased consumers’ attraction to self-medicate rather than visit a physician. But because it was therapeutically inert, their conditions likely festered or worsened. From 1917-1934 FDA took action against Pabst’s for misbranding 23 times!

Peralga

Peralga, marketed as a weight-loss remedy, was one of many such products that contained amidopyrine and barbiturates. In certain individuals (typically women), the combination of these drugs could cause agranulocytosis, a dangerous loss of white blood cells, which severely limited their ability to fight off infection and often led to death.

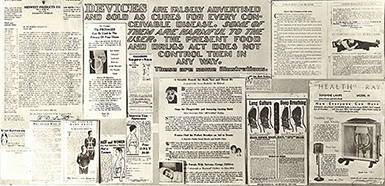

Quack Devices

Quack Devices became increasingly popular in the decades after the First World War thanks to new technological capabilities and marketing media – especially, the radio. Advertisements falsely promised consumers an easy cure for virtually any complaint imaginable, from cancer to “mouth breathing,” but because the Pure Food and Drugs Act did not apply to devices, the FDA could not regulate them. By the early 30s, the agency formalized a collaborative office with the U.S. Postal Service to prosecute quack devices peddlers for mail fraud.

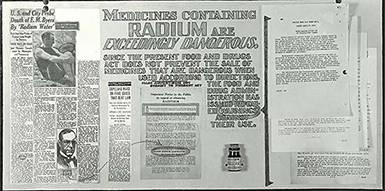

Radithor

Radithor claimed to treat impotence and dozens of other diseases. It made headlines following news of the horrifying death from radium poisoning of Eben Byers, a prominent businessman and athlete who consumed Radithor for years, and many others used the treatment. Even though Radithor was extremely dangerous, it was accurately labeled as a “radioactive water” and thus legal under the 1906 Act.

Sleepy Salts

Sleepy Salts was one of many quack “reducing aids” that was merely a powerful laxative. It promised to help consumers meet the demands of 20th century life and to remain forever young, by promoting “clearness of mind and swift graceful body.” FDA won a seizure action against the product because promotional materials shipped with the product made unverifiable therapeutic claims, including that it could treat rheumatism, neuritis, arthritis and renal problems.

Tanlac

Tanlac, a 36 proof mixture of wine, glycerin and bitter herbs, was marketed as a “system purifier,” laxative and treatment for catarrh, a common complaint targeted by patent medicines that was an elaborate euphemism for mucous. The American Medical Association described Tanlac as a “sky-rocket in the pyrotechnics of fakery,” that relied on extensive advertising and false testimonials to dupe consumers.

Vapo-Cresolene

Vapo-Cresolene, marketed in various forms since the late 19th century, vaporized a coal-tar by-product in the included apparatus to allegedly treat a host of diseases through inhalation, including diphtheria and influenza. Though the FDA successfully moved against this product under the 1906 Act, the manufacturer transferred the therapeutic claims from the label to Vapo-Cresolene’s advertising.

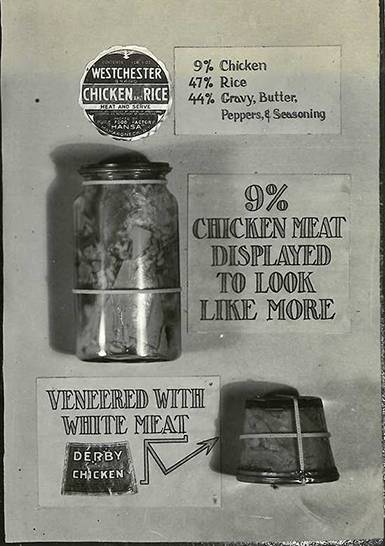

Veneered Chicken

Was a deceptive packaging scheme that was typical of the time. The more expensive white mean was placed in this jar in a thin outside layer that disguised the fact that most of the contents included dark meat.