Advancing Our Understanding of How Drug Promotion Influences Consumers and Health Care Providers

CDER researchers are exploring the development of validated instruments to measure perceptions of direct-to-consumer drug advertisements, investigating the effects of imagery in these ads, and uncovering factors that can influence whether deceptive ads are reported to FDA.

Advertisements for prescription drugs are pervasive in the United States, and both health care providers and consumers are exposed to a tremendous amount of information promoting the benefits of these products. These ads can convey useful information about treatment options, but at times, they may also contain misleading information. Although FDA does not generally approve prescription drug advertising and promotion before it is made public, the agency is charged with regulating promotion of prescription drugs. Reviewers in CDER’s Office of Prescription Drug Promotion (OPDP) continually monitor prescription drug advertising and promotional labeling to ensure that it is neither false nor misleading, follow up on complaints about alleged promotional violations, and initiate compliance actions.

Vital to this regulatory effort is understanding how the audience perceives and interprets these promotional communications and ultimately responds to them. OPDP leads a diverse and dynamic research program to investigate these questions. Recent research accomplishments, led by OPDP, are discussed below.

The Role of Images

Direct-to-consumer prescription drug promotion often includes images—to convey drug effectiveness, for example, visually showing improvements in the patient’s symptoms after treatment. To better understand how images may in some instances mislead people and how misperceptions can be avoided, OPDP researchers and collaborators conducted a randomized studyExternal Link Disclaimer in which more than 1,800 participants (60 years and older) viewed ads for fictitious drugs to treat psoriasis or wet age-related macular degeneration (AMD). Individuals were randomly assigned to view drug ads that either 1) contained no images; 2) contained images that accurately reflected the efficacy information presented in in the ad verbiage; or 3) contained images that exaggerated the drug efficacy verbiage (Figure 1). Furthermore, the ads either omitted quantitative information about the drugs’ benefits (e.g., “In clinical studies, Vistasin shrank wet AMD patients’ blind spots…”) or contained quantitative information about the drug’s benefits (e.g., “In clinical studies, Vistasin shrank wet AMD patients’ blind spots by an average of 65%, compared to an average of 45% with another prescription drug…”). The online participants then responded to questions about ad content regarding the extent of improvement likely to be attained though treatment.

Figure 1. Assessing the effect of imagery in drug ads. To understand how consumers respond to visual information in direct-to-consumer drug advertisements, OPDP researchers created ads for hypothetical drugs to treat wet age-related macular degeneration and psoriasis. Some of the ads contained visual images that accurately reflected the efficacy claims in the ads, while others contained either no images or images that exaggerated the improvement that would be attained. The accurate before and after images for a drug to treat macular degeneration (left) and corresponding exaggerated images that were used in the study are shown (right). Learn moreExternal Link Disclaimer.

The study results underscored the important role of images in drug ads: For both medical conditions tested, participants who viewed ads containing exaggerated images of beneficial effect were more likely to have exaggerated perceptions of the drug’s efficacy. The presentation of quantitative information increased participants’ understanding of drug efficacy, and in some cases even counteracted the effect of exaggerated images. Higher numeracy in participants was also associated with better understanding and recall of the ads’ claims.

The researchers concluded that drug companies who create drug advertisements as well as regulators who are responsible for reviewing promotional material should pay special attention to ensuring that images accurately reflect drug efficacy. Additionally, prescribers should ensure that patients properly understand the efficacy of a drug when considering treatment options.

Developing Valid Measures of How Ads Are Perceived

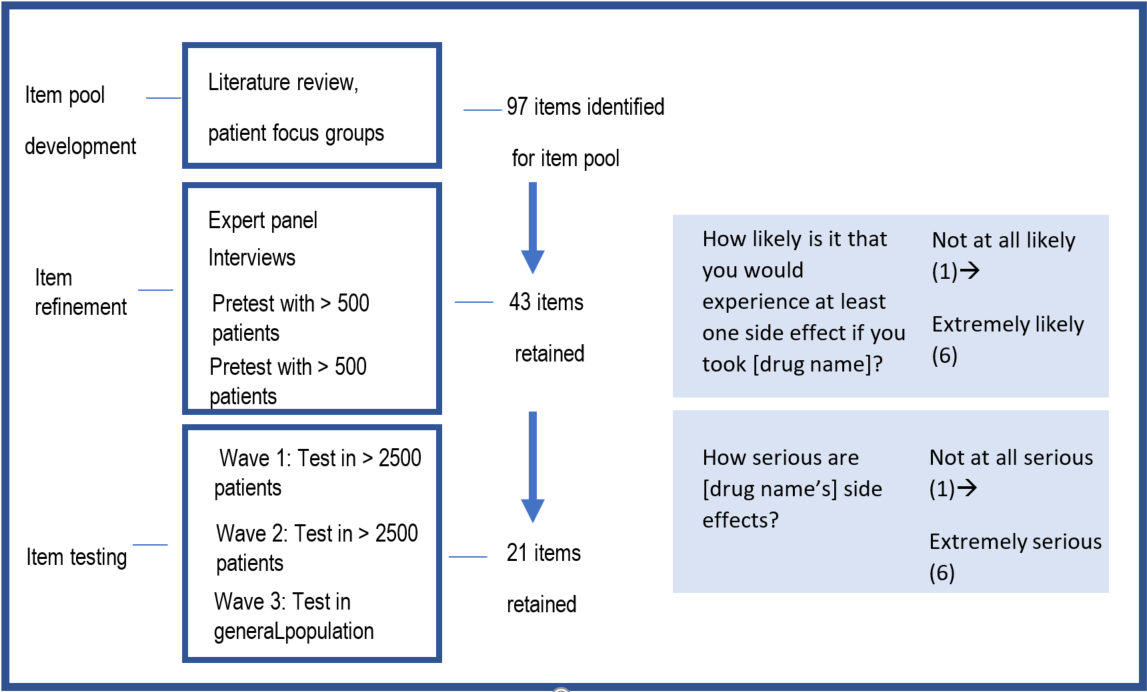

Reliable instruments for measuring consumer perceptions of prescription drug risk, efficacy, and benefit are essential tools for rigorously evaluating direct-to-consumer prescription drug promotion. Building from outcomes of a literature review, expert input, and focus groups, OPDP researchers recently created a large pool of candidate questionnaire items, including 31 on perceived risk, 32 on perceived efficacy, 29 on perceived benefit, and 5 on risk/benefit tradeoff. Items pertaining to risk and efficacy were categorized into those related to likelihood, magnitude, onset of risk or beneficial effect, or duration of risk or beneficial effect.

To evaluate these candidate questionnaire items, the researchers created a set of print and TV advertisements for hypothetical prescription drugs for high blood pressure or chronic pain. Participants viewed one of these ads for a drug that was either high or low efficacy/benefit and was either high or low risk. Patient and general population responses to the questionnaire items were evaluated in three waves of randomized testing (see Figure 2). The researchers analyzed participant responses to identify those questionnaire items that were most meaningful (based on measures of validity and reliability); from the initial pool of 97 items, 21 items were ultimately retained (see the two example items presented in Figure 2). The researchers suggest these items can be used by those seeking to understand consumer perceptions of direct-to-consumer advertising, regardless of the advertising medium used or the condition the drug is meant to treat. Furthermore, these robust measures may prove to be valuable in other contexts, such as in patient-provider conversations about medications, at the pharmacy, and for assessing label comprehension.

Figure. 2. Building from outcomes of a literature review, focus groups, and expert input, OPDP researchers and collaborators developed a pool of 97 candidate items capturing perceived risk, perceived efficacy, perceived benefit, or risk/benefit tradeoff items. A set of direct-to-consumer advertisements (in print or television versions, typical of direct-to-consumer ads) for hypothetical medications for high blood pressure or chronic pain were created. These ads conveyed information about risks, benefits, and efficacy, and within each print and television ad the researchers manipulated the efficacy and benefit information (high or low efficacy/ benefit) and the risk information (high or low risk).

The researchers used several statistical approaches to measure key attributes of the items. Details of the ad development, the questionnaire items, randomization of participants, and statistical assessment of reliability and validity can be found hereExternal Link Disclaimer.

Three successive waves of testing allowed researchers to narrow the item pool to 21 items that could be of use in assessing responses to direct to consumer advertising among patients with both symptomatic and asymptomatic health conditions, and in response to both television and print direct-to-consumer prescription drug advertisements.

Two of the items that were retained in the final set are shown at right.

Detection and Reporting of Deceptive Drug Practices: A Role for Physicians and Consumers

FDA’s Bad Ad Program provides an avenue, primarily for health care providers, to report false or misleading prescription drug promotion directly to FDA. To understand the extent to which health care providers and consumers can detect deceptive promotions and whether they believe false advertising should be reported to FDA, OPDP researchers constructed mock pharmaceutical websitesExternal Link Disclaimer that contained information about efficacy and risks for two fictitious drugs, one described as treating chronic pain and one as treating obesity. The website for the chronic pain drug contained a varying number of deceptive claims and tactics (0, 2, or 5), and the website for the obesity drug contained either no deceptive claims or an implicitly or explicitly false claim. The researchers conducted a randomized study of primary care physicians and consumers to measure their ability to detect, and their inclination to report, deceptive prescription drug promotion.

Although both physicians and consumers had some ability to detect deceptive claims, the researchers found that over one-third of consumers and one-quarter of physicians exposed to websites with five deceptive claims and tactics indicated that no inaccuracies were present. Furthermore, half of the physicians who saw websites with explicitly false information, and three-quarters of those who saw implicitly misleading information, indicated that the promotions contained no inaccuracies.

Although the majority of consumers and physicians indicated they would take some action if they came across misleading drug product advertisement, one-quarter of the physicians and at least one-third of consumers (across both studies) indicated that they would not take action. This reticence could be, in part, due to the low awareness of the Bad Ad Program among physicians and consumers (less than 10% and 4% for physicians and consumers, respectively).

Based on these findings, the researchers suggested that FDA could consider, as a part of the Bad Ad Program, to solicit user-friendly consumer reporting and implement public awareness campaigns targeted to both consumers and physicians, and that taking these steps could facilitate the reporting of deceptive advertising to FDA. The ultimate goal would be to generate more accurate prescription drug information across the promotional media landscape.

How does this research advance public health?

CDER researchers in OPDP within the Office of Medical Policy and their collaborators are developing and applying rigorous experimental methods to advance our understanding of how consumers and health care providers perceive and respond to prescription drug promotion. The insights gained by this research can help inform guidance, enhance review of drug promotion, and ultimately help ensure that consumers and health care providers have the information they need to make informed health decisions.