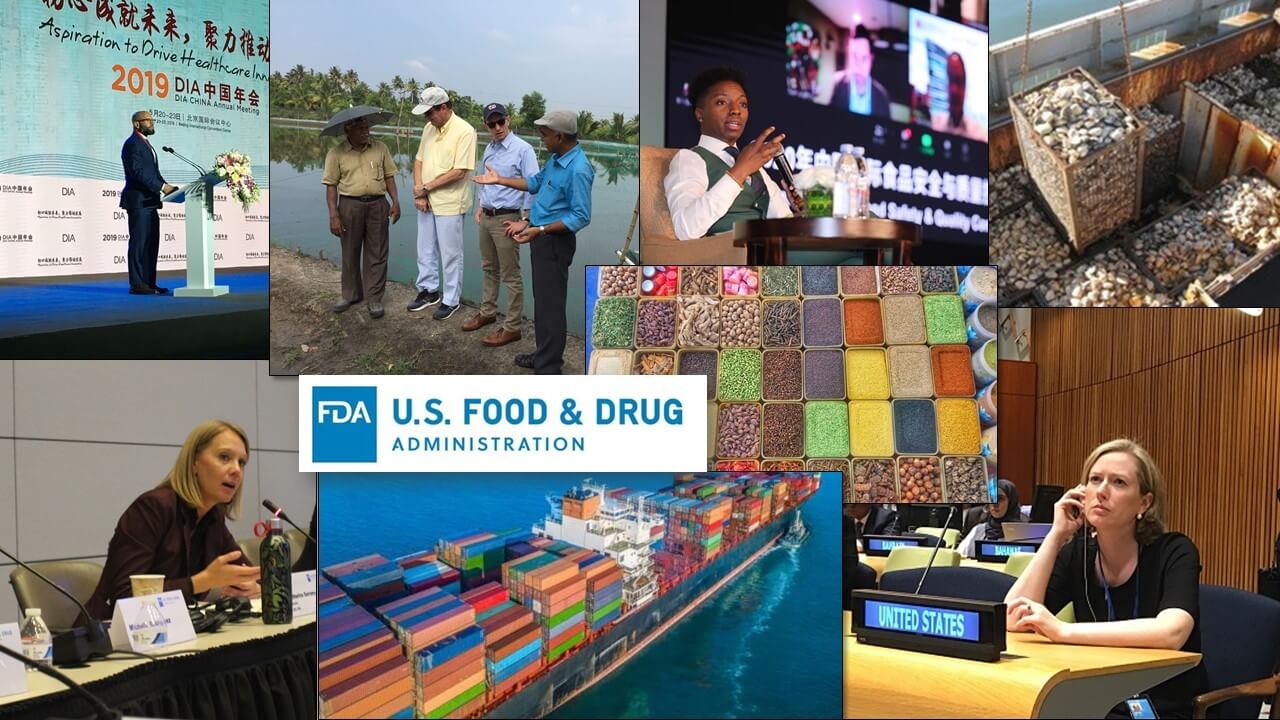

Global Considerations and Engagements: How FDA’s Global Work is Advancing Public Health

FROM A GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE

By Anna Abram and Mark Abdoo

January 15, 2021

We live in a globalized world that requires FDA to take a global perspective. The multinational landscape for human and animal drugs, devices, food and feed, and cosmetics require a global approach and cooperation with trusted regulatory partners abroad to achieve FDA’s vital public health mission.

The COVID-19 pandemic has only increased and underscored the importance of FDA’s global work. In mid-March, early in the COVD-19 global pandemic, regulatory authorities from around the world convened to discuss ways to facilitate the development of COVID-19 vaccines and to commit to work towards greater regulatory convergence with the goal of timely vaccine development to effectively respond to the global pandemic.

We’re proud of the contributions our FDA colleagues are making through this work in our foreign offices. Our Europe Office in the FDA’s Office of Global Policy and Strategy (OGPS) worked with the European Medicines Agency (EMA) to organize that historic March workshop of the International Coalition of Medicines Regulatory Authorities (ICMRA). And it’s just one of dozens of ways in which OGPS staff has engaged in a meaningful way during the pandemic.

Elsewhere, OGPS staff in our China, India, and Latin America offices have been key to important bilateral exchanges; assisting embassy-led supply chain taskforces; advising colleagues at the embassy about FDA-regulated commodity sources in-country that could meet the shortages of personalized protective equipment; and identifying alternate suppliers to support various U.S. response initiatives.

FDA’s Evolution Since the 20th Century

The FDA’s ability to respond so effectively on the global stage during this public health crisis is the result of decades of groundwork to incorporate a global perspective in our policy and programmatic work.

Consider what the world looked like for the FDA in the mid-20th century. The agency’s public health mission was largely confined within the borders of the United States since most FDA-regulated products were grown, produced, studied, and manufactured here at home. But the waning decades of the 20th century saw the rise of multinational corporations, the increasingly international nature of scientific research, and an explosion in the globalization of production. As FDA-regulated industries became more global, several regulatory systems around the world became increasingly competent and sophisticated. Some were modeled on the FDA itself, some even changed their official name to FDA, while others evolved along alternative pathways, challenging FDA to find new ways to work with a variety of regulatory counterparts.

The FDA’s operating model for this more globalized world began after World War II with the birth of the United Nations and its specialized bodies, the World Health Organization (WHO), the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, and the World Organization for Animal Health. The FDA worked to set high standards in international trade and negotiated bilateral understandings to safeguard the quality of drugs and the safety of food, feed and other regulated products.

In the 1960s, one or two staff members handled foreign inquiries and visits to the FDA. In 1979, the FDA formed the International Affairs Staff in the Office of the Commissioner to coordinate FDA’s international engagements globally. Just a year later, the WHO and the FDA played host to the first International Conference of Drug Regulatory Authorities, or ICDRA. With the success of ICDRA, other commodity-specific international organizations would follow, including the ICMRA.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the FDA created global arrangements with regulatory authorities and industry to harmonize standards and regulatory standards for both human and animal medical products. The agency was also tasked with assisting in outreach to more generalized multilateral organizations including the World Trade Organization (WTO), which was established in 1995. The FDA’s bilateral regulatory relationships were further enhanced when the FDA began signing a series of confidentiality commitments to allow sharing of certain types of non-public information, beginning with the foundational agreement with the EMA in 2003.

The Establishment of FDA’s Foreign Offices

While the FDA was forging arrangements with our regulatory counterparts, import shipments of FDA-regulated products were escalating - by 13% in 2000 and even more since then. This rise in the volume of imported products led to a wave of public health tragedies, including those caused by contaminated heparin and by melamine-laced pet food, both coming from China. To better assure the safety and effectiveness of the many FDA-regulated imported goods entering the United States, the FDA set up offices in countries with a high percentage of exports to the United States. China and India were the first foreign offices, both opened in late 2008. They were soon followed by offices in Latin America and Europe. The Office of International Programs or OIP, formed in 1999 and the successor to the International Affairs Staff, oversaw these offices.

The foreign offices became a critical presence for the FDA abroad, responding to disruptions caused by disasters, outbreaks or other events; engaging with local and regional stakeholders to strengthen host-country regulatory frameworks and increase industry’s compliance with the FDA’s safety, quality and efficacy standards; collecting data; conducting foreign inspections; and providing the FDA with in-country information regarding manufacturing and other key factors that might influence public health.

A few years after the formation of the foreign offices, both OIP and the Office of Regulatory Affairs were folded into an overarching new directorate, the Office of Global Regulatory Operations and Policy. But over time the FDA recognized there was a need for greater international policy coherence and communication across the Agency. Nearly two years ago, the FDA established a new global office, OGPS, by augmenting and redesigning OIP within the Office for Policy, Legislation and International Affairs, as part of a broader reorganization of the FDA Commissioner’s office.

Today, OGPS is still charged with overseeing the foreign offices, engaging with international stakeholders, working with multilateral organizations such as the WTO, and negotiating confidentiality agreements. But in addition, OGPS is playing a critical role in working to achieve greater policy coherence and mutual understanding across FDA Centers and Offices, as well as across the world. The public health value of this enhanced collaboration is being realized as we have seen with our Revised Pharmaceutical Annex to the Mutual Recognition Agreement (MRA) with the EU, the Pharmaceutical Annex to our MRA with the UK, and our shellfish equivalence determination, also with the EU.

The importance of this focus and collaboration has been repeatedly affirmed over the years and continues to be critical to our public health endeavors. Now, more than ever, our work with our global regulatory counterparts to confront the most pressing public health challenges is vital to achieving the FDA’s mission.

Anna Abram is Deputy Commissioner for Policy, Legislation, and International Affairs

Mark Abdoo is Associate Commissioner for Global Policy and Strategy