Testimony | In Person

Event Title

Modernizing FDA's Regulation of Over-the-Counter Drugs

September 12, 2017

Testimony of Janet Woodcock, M.D, Director, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research

Before the House Energy and Commerce Committee, Subcommittee on Health

September 13, 2017

INTRODUCTION

Good morning Chairman Walden, Ranking Member Pallone, and members of the Subcommittee. I am Janet Woodcock, Director of the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) at the Food and Drug Administration (FDA or the Agency), which is part of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Thank you for the opportunity to be here today to discuss potential reforms to the over-the-counter (OTC) monograph system and a new OTC monograph user fee program.

OTC drugs have long provided an efficient, low-cost way for Americans to take care of every-day health needs, without the need to visit a doctor and obtain a prescription. OTC regulation is considered appropriate for most drugs that can be safely administered without the supervision of a health care practitioner. FDA regulates most of the drugs on drug store shelves under the “OTC monograph system,” though manufacturers do have the option to file a new drug application (NDA) in lieu of using the OTC monograph system for OTC products. FDA publishes monographs that provide a rulebook for marketing safe and effective products containing particular active ingredients for specific OTC conditions. Products that conform to the monograph rules and other relevant requirements are not required to be reviewed by FDA before marketing. This contrasts with the NDA system, where sponsors of drugs must submit an application to FDA and obtain approval prior to marketing. The OTC Monograph system provides lower regulatory burden for industry and helps to keep OTC drug costs low through the extensive array of potential products that final monographs can cover.

When it was first created over 40 years ago, the monograph system was relatively efficient, permitting timely monograph development to address safety and effectiveness issues. As product innovation unfolded, however, the monograph system has not kept up, leaving a system that does not well-serve consumers or industry. FDA still has not been able to complete many monographs begun decades ago. Nor has it been able to make timely monograph modifications to account for evolving science and emerging safety issues, or to accommodate product innovation or marketing changes. Approximately one third of the monographs are not yet final, and several hundred individual ingredients (monographs can include multiple ingredients) do not have a final determination of safety and effectiveness. In addition, a number of planned safety labeling changes for monograph ingredients have not yet taken place while similar changes have already been made to prescription drugs containing the same ingredient. Finally, restrictions in the monograph system may discourage manufacturers from innovating.

Reforms to modernize and support FDA’s OTC monograph activities are needed to better serve patients, consumers, and industry. Stakeholders from across patient groups, healthcare providers, public health groups, and industry support reforms to streamline and improve the timeliness of review activities, spur innovation on behalf of consumers, and enable the Agency to better respond to urgent safety issues. FDA agrees that these changes will better protect the public health.

In addition to structural reforms, the oversight of the OTC marketplace must have more resources if FDA is to fully realize the goals of reform and ensure the safety and effectiveness of OTC drugs, as well as support innovation by industry. Together with industry, FDA has developed a proposed OTC monograph user fee program, modeled on the successful Prescription Drug User Fee Act (PDUFA) program which, over the past 25 years, has ensured a more predictable, consistent, and streamlined premarket program for industry and helped speed access to new safe and effective prescription drugs for patients. Following the success of PDUFA, Congress enacted additional user fee agreements (UFAs), such as those that cover medical devices, generic drugs, and biosimilar drug products, as well as animal drug products and generic animal drug products. Under a user fee program, industry agrees to pay fees to help fund a portion of FDA’s drug review activities while FDA agrees to overall performance goals, such as reviewing a certain percentage of applications within a particular time frame. As a result of the continued investment of UFA resources, FDA has dramatically reduced the review time for drug products without compromising the Agency’s high standards for demonstration of safety, efficacy, and quality of such products. New legislation is needed to allow FDA to establish a similar program for OTC monograph drug products that will help ensure a better resourced and more streamlined, efficient process.

BACKGROUND

OTC Review is one of the Agency’s largest and most complex regulatory programs.

The OTC Drug Review program was created by FDA in 1972 to facilitate the efficient review of hundreds of thousands of OTC medicines. Rather than approve each product, as typically is done for prescription drugs and certain OTC drugs, the OTC Drug Review develops monographs for various therapeutic categories (e.g. internal analgesics, cough/cold products). The monographs establish conditions, such as active ingredients, indications, dosage form and labeled directions, under which an OTC drug is generally recognized as safe and effective (GRASE) for use. There are three categories for OTC products: Category I includes products that are GRASE. Category II includes products that are not GRASE. Category III include products for which more data is needed to determine whether they are GRASE. An OTC medication that meets the specific conditions contained in the monograph is not required to be approved by FDA before marketing.

The OTC Drug Review Program has proven to be one of the largest and most complex regulatory programs ever undertaken at FDA. It now consists of approximately 88 simultaneous rulemakings in 26 broad therapeutic categories that encompass hundreds of thousands of OTC drug products marketed in the United States. Collectively, these monographs cover some 800 active ingredients for over 1,400 different uses, ranging from antacids to diaper rash creams, and from analgesics to cough/cold products.

The current OTC Review system is slow and antiquated.

OTC medications play an increasingly vital role in our health care system. Although the current system has provided consumers with access to a wide variety of OTC medicines for decades, OTC products have become scientifically more challenging to regulate and the regulatory framework for OTC monograph products has become increasingly difficult to administer. Challenges in the current system include:

- Burdensome, lengthy, multi-step processes to gather and evaluate data that take many years to complete;

- Limitations on what new products can be marketed under the OTC Review; and

- Limited resources to carry out the Agency’s responsibilities.

Together, these challenges are responsible for several widely-recognized shortcomings of the OTC Review, including:

- Inefficient and time consuming process for completing safety and effectiveness reviews of OTC monographs;

- Limited speed and flexibility in responding to urgent safety issues;

- Challenges in keeping pace with evolving science; and

- Challenges in accommodating innovation.

Monograph rulemaking takes much too long.

Rulemaking can be a particularly inefficient process for scientific decisions, where new information frequently emerges over time, often requiring FDA to start the rulemaking process over to account for evolving science.

The OTC Drug Review was intended to be a three-step, public notice and comment rulemaking process. As originally implemented, the process began with publication in the Federal Register of reports from an outside panel of experts. These reports were published in Advance Notices of Proposed Rulemakings, or ANPRs. Public comments on these reports were submitted by the drug industry, by medical professionals, and by consumers – anyone with an interest in the topic of the report could submit comments. FDA considered the reports, comments, any new data and information, revised the ANPR accordingly, and published the revisions as a proposed rule. The proposed rule is also known as the tentative final monograph, or TFM.

In response to the TFM, a second round of comments was received and evaluated. Following submission of comments to the TFM, the last step of the process was for FDA to analyze the comments and data that were submitted in response to the TFM, and to revise the monograph and publish it as a final rule. Once published, the final monograph would contain the regulations that establish the conditions under which a category of OTC drugs is considered GRASE. The final monographs would then be published in the Code of Federal Regulations in Title 21, Food and Drugs.

Although some monographs in the OTC drug review were finalized using this three-step public notice and comment rulemaking process, for many other monographs, the reality has deviated from this plan to account for distinctions between products contained in the same monograph. Figure 1 (below) shows the journey that the external analgesic drug product monograph has taken. This lengthy and circuitous path is not unusual.

Burdensome, Multi-step Rulemakings

| Published | Fed Reg citation | Topic |

|---|---|---|

| 12-4-79 | 44FR69768 | ANPR for External Analgesic Drug Products |

| 2-5-80 | 45FR7820 | Correction |

| 9-26-80 | 45FR63878 | Reopening of administrative record |

| 9-7-82 | 47FR39412 | Reopening of administrative record |

| 12-7-82 | 47FR54981 | Correction |

| 12-28-82 | 47FR57738 | Extension of comment and reply periods |

| 2-8-83 | 48FR5852 | TFM (Tentative Final Monograph = Proposed Rule) |

| 3-11-83 | 48FR10373 | Correction |

| 10-2-85 | 50FR40260 | Amend TFM to add male genital desensitizer indication |

| 7-30-86 | 51FR27360 | Amend TFM to add seborrheic dermatitis and psoriasis indication |

| 8-25-88 | 53FR32592 | Amend TFM warnings and directions for external anal itching |

| 4-3-89 | 54FR13490 | Amend TFM to remove astringent drug products |

| 10-3-89 | 54FR40818 | Amend TFM to add poison ivy, poison oak, poison sumac, and insect bite indications |

| 1-31-90 | 55FR3370 | Amend TFM to address fever blister and cold sore indications |

| 2-27-90 | 55FR6932 | Amend TFM to make hydrocortisone 1% OTC |

| 3-27-90 | 55FR11291 | Correction |

| 6-20-90 | 55FR25234 | Amend TFM to address treatment and prevention of diaper rash |

| 8-30-91 | 56FR43025 | Hydrocortisone; Notice of Enforcement Policy |

| 6-19-92 | 57FR27654 | FR (Final Rule) Male genital desensitizer |

| 12-18-92 | 57FR60426 | FR (Final Rule) Diaper rash labeling |

| 8-29-97 | 62FR45767 | Amend TFM to add warning about diphenhydramine |

| 11-19-97 | 62FR61710 | Reopening of administrative records to consider new data |

Figure 1

Some of these entries show that the administrative record was reopened to accept new data; the comment period was extended; and the TFM was amended to add new indications or uses, to remove some ingredients that were moved to other monographs, and to incorporate changes prompted by new scientific data, including new safety warnings. You will notice that some indications became final even though the entire monograph has not become final. This example illustrates the complexity that FDA now faces with trying to keep monographs updated to address the safety and effectiveness of OTC drugs.

There is a lack of speed and flexibility in responding to urgent safety issues.

Using the current monograph process to address safety labeling changes and other public health priorities limits FDA’s ability to address safety issues for OTC drugs in a timely manner.

Under the current monograph system, FDA is limited in its ability to require safety issues to be definitively addressed, unless it goes through rulemaking. While not a substitute for final rulemaking, wherever possible FDA has acted to address these public health issues through other methods such as consumer education efforts and guidance to industry. A few recent examples include:

- Safety of pediatric cough and cold products

FDA has published a number of consumer updates (available on FDA’s website) to inform consumers on the safe and effective use of OTC products due to reports of harm, and even death in young children. Examples include: - Adverse events related to use of codeine for the treatment of cough

FDA held advisory committee (AC) meetings on December 10, 2015, and September 11, 2017, to review pediatric codeine use. Codeine carries serious risks, including slowed or difficult breathing or death, which appear to be a greater risk in children younger than 12 years (Codeine and Tramadol Can Cause Breathing Problems for Children). These meetings followed a number of communications issued by FDA to inform both consumers and health care providers about the safe use of codeine in children. - Serious skin reactions with acetaminophen

In 2013, FDA published a drug safety communication alerting the public to serious skin reactions with acetaminophen. For prescription drugs marketed under the NDA process, FDA was able to take action quickly to have a warning added to the label. For OTC monograph drugs, which comprise the majority of the market, the Agency could not have generally required the necessary safety changes without undertaking a lengthy rulemaking. In order to more quickly encourage appropriate labeling changes, the Agency opted to issue a guidance instead, requesting that manufacturers add a warning to their labels.

Although these non-rulemaking approaches have been helpful as alternative ways to effect safety labeling changes and to notify consumers of safety concerns, these approaches are far from optimal because they do not result in changing the relevant monograph to reflect the new safety labeling.

To address these challenges with the existing OTC monograph system, FDA, industry, and other stakeholders have discussed a series of potential reforms with Members of Congress. These reforms would:

- Streamline the process for adopting OTC monographs and for amending existing monographs;

- Provide a special mechanism for rapidly responding to urgent safety issues;

- Eliminate certain barriers to innovation and provide a more nimble process for their review by FDA; and

- Reduce the backlog of unfinished monographs, for example by finalizing those FDA rulemakings that reached the stage of a Tentative Final Monograph.

Monograph reform can streamline processes, but will not address resource challenges.

As noted previously, the OTC monograph program is one of the largest and most complex regulatory programs ever undertaken at FDA. But FDA has very limited resources to carry out the Agency’s responsibilities in the OTC monograph program. With current resource levels, FDA struggles to meet the requirements of Congressional mandates, keep pace with science, and meet public health needs for monograph products in a timely fashion. The OTC monograph review does not currently receive user fee funding, and funds from other user fee programs cannot be used to support monograph work.

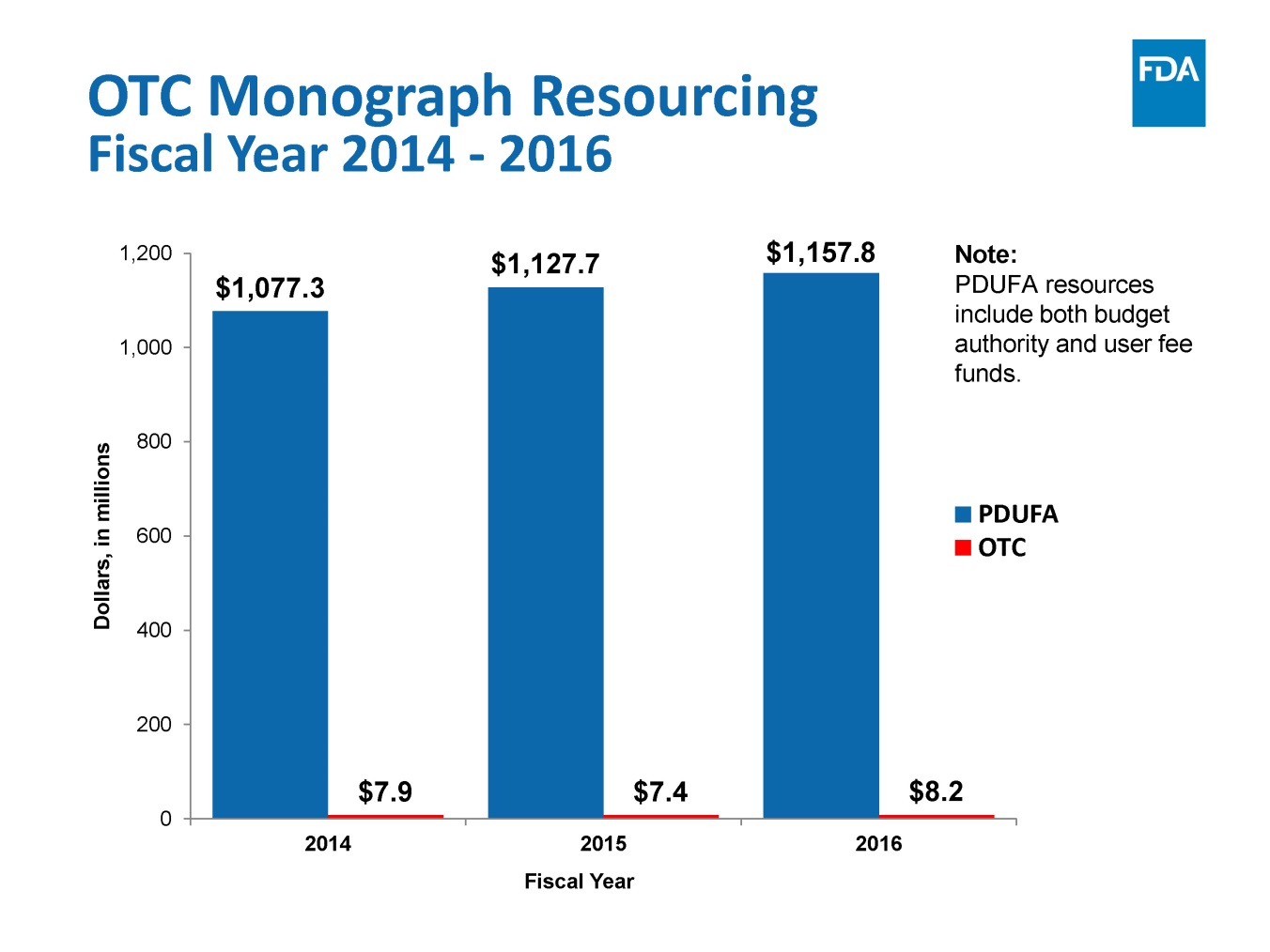

For a perspective on the resource challenges faced by the monograph program, the Agency currently spends approximately 40 times as much budget authority (BA) on the process of reviewing PDUFA products as it does on OTC monograph products. In FY2016, the Agency spent $320.9M in BA reviewing PDUFA products and $7.9M in reviewing OTC monograph products. Because a user fee program is intended to supplement BA spending and not to supplant it, in that year, the Agency had access to additional funds from PDUFA user fees in the amount of $836.9M. The total Agency spending on the PDUFA program was therefore $1.16 billion, despite the fact that there are far more OTC monograph drug products than there are branded prescription drug products (see Figure 2 below).

Figure 2

OTC Monograph Reforms and User Fee Program would address these challenges.

The proposed OTC Monograph Reforms and User Fee Program are designed to address the regulatory challenges mentioned above, as well as to provide benefits to the public health and to regulated industry. Potential benefits of OTC Monograph reform with supporting user fees include:

- Timely determination on the conditions for GRASE general recognition of safety and effectiveness that would cover thousands of marketed monograph drug products;

- Ability to address safety issues in a more timely and efficient manner;

- Ability to consider certain OTC product innovations proposed by industry;

- Streamlined ability to update monographs to provide for modern testing methods that can improve the effectiveness of products available to consumers;

- Development of information technology infrastructure for submission, review and archiving of monograph information;

- Development of a modern, useful, transparent Web interface; and

- Increased ability to respond to monograph-related concerns from the public and industry.

OVERVIEW

We have worked with numerous stakeholders, including consumer, patient, academic research, and health provider groups, and various representatives of industry to get their input on the proposed OTC Monograph Reform and User Fee Program.

At the request of Chairman Lamar Alexander of the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions in 2015, FDA began discussions with industry to discuss ways to reform the OTC Monograph review program. As part of this process, FDA solicited input from and worked with various stakeholders, including representatives from consumer, patient, academic research, and health provider groups, and engaged in discussions with the nonprescription drug industry to help Congress develop authorization language, with user fees, that would launch a reformed OTC Monograph drug review program. In addition, FDA held a public stakeholder meeting and two public webinars to obtain additional feedback and share progress of discussions regarding user fees and goals. The final proposed agreement and the goals to which FDA and industry agreed to were transmitted to Congress on June 7, 2017. (Please see Appendix for "Goals Letter" that details our goals, implementation plan, and timelines.)

The goals of the OTC Monograph User Fee program are to:

- Build a basic infrastructure (hiring, training, and IT) to meet the goals of monograph reform;

- Enable industry-initiated innovation (including innovation order requests, development meetings, timelines, and performance goals);

- Enhance communication and transparency;

- Enable streamlining of industry and FDA safety efforts;

- Enable efficient completion of final GRASE determinations for Category III drugs requested by industry or initiated by FDA; and

- Develop and incorporate measures to track successes and Agency accountability.

FDA estimates that the fees collected under the OTC Monograph User Fee program would start at $22 million in Year 1 and gradually increase to a steady state of $34 million by Year 4. For the sake of comparison, in FY18, the prescription drug user fee program is projected to be over $800 million per year and the generic drug user fee program is projected to be just under $500 million per year; the biosimilar drug user fee program, which is projected to be at around $40 million, is much closer in size to the proposed OTC monograph program.

OTC manufacturers would pay an annual facility fee under the proposal, and there would be an additional fee each time a sponsor submitted what is known as an OMOR – Over-the-counter Monograph Order Request (this is analogous to the NDA under PDUFA). The fee amounts would be set before the beginning of each fiscal year, and would be set at an amount to generate the required level of revenue each year. The per-facility fee will be a function of the number of facilities when the program goes live.

Performance and Procedural Goals

The performance and procedural goals and other commitments specified in the Goals Letter apply to aspects of the OTC monograph drug review program that are important for implementing the aforementioned policy reforms and for facilitating timely access to safe and effective medicines regulated under the OTC drug monograph. FDA is committed to meeting the performance goals specified in the goals document under the baseline assumptions described and to continuous improvement of its performance. FDA and industry would periodically assess the progress of the OTC monograph review program. This would allow FDA and industry to develop strategies to address emerging challenges to ensure the efficiency and effectiveness of the OTC monograph drug review program.

Infrastructure Development: Hiring, Training, and Growth of Effective Review Capacity

The goals document outlines hiring targets for each of the first five years of the proposed monograph user fee program. FDA would work toward these hiring goals. An important concept is that of the growth of effective review capacity. A newly hired scientist does not come to FDA with all the specialized skills and knowledge required to be an effective scientific reviewer. FDA scientific review work is highly technical and specialized. It requires knowledge and skills that are acquired through training at FDA, and typically takes approximately two years for a new staff person to become fully effective in monograph review work. This training process occurs simultaneously with assigned review work, with increasing review workload as a new reviewer gains experience and training. As these new employees come on board and are trained, total FDA effective review capacity for the monograph will increase in a measured fashion.

During FY15, FY16, and FY17, essentially all of FDA’s monograph review capacity has been dominated by the following three activities:

- Statutory requirements of the Sunscreen Innovation Act;

- Court-mandated requirements of the consent decree pertaining to antiseptic drug products; and

- Urgent safety activities.

During FY18 and FY19, FDA will continue to have court-mandated obligations under the antiseptic consent decree. Congressionally-mandated obligations will also continue under the Sunscreen Innovation Act during those years (and perhaps subsequent years as well), unless Congress chooses to amend that law as part of the OTC monograph reform process because sunscreens are OTC products. Safety activities, for both pressing issues and routine pharmacovigilance, are continuous at FDA.

There will also be numerous implementation activities for monograph reform that would absorb additional review capacity in the first three years of a monograph user fee program. Therefore, FDA expects to have built sufficient effective review capacity to begin to have timelines and performance goals for review activities anticipated to be part of the steady state of a monograph review program beginning in years four and five of the program (and to a limited extent in year three).

Development and Implementation of an Information Technology Platform

The OTC Monograph User Fee program would involve the development of a new IT platform. FDA would leverage an existing FDA IT platform to develop an IT system for the OTC Monograph User Fee program. FDA would work with industry to develop specifications for a public-facing IT dashboard, and would establish a fully functioning IT platform for OTC drug monograph review within five years of the program.

In order to maximize the efficiency of the monograph review process, all monograph submissions would be electronic. FDA would modify existing guidance regarding the content and format of submissions to provide clarity to industry on how to structure its submissions.

Enabling Industry-Initiated Innovation

Innovation under the current monograph framework has been difficult. Under monograph reform, sponsors would be able to submit data packages (OMORs) to FDA, with requests that FDA issue an administrative order for a change to a monograph. There would be two types of Innovation OMORs, referred to as Tier One Innovation OMORs and Tier Two Innovation OMORs. The Goals Letter provides examples of each type of Innovation OMOR, but basically, most Innovation OMORs will be Tier One OMORs, and a few specific types of less resource-intensive OMORs would be Tier Two.

Innovation OMORs for new active ingredients would require an eligibility determination, to show that there is a sufficient marketing history of the drug being safely used in an OTC setting under comparable conditions of use, e.g., in other countries. Industry could submit a request for an ingredient’s eligibility determination well in advance of submission of the OMOR. Minimum advance submission periods for eligibility determination requests are specified in the Goals Letter. Other types of innovations would not require an eligibility determination.

In-Review Meeting

For filed Innovation OMORs and for filed industry-requested GRASE Finalization OMORs, FDA would schedule an in-review meeting to be held between the requestor of the OMOR and FDA. The Goals Letter details submission requirements and timelines.

Guidance Development for Innovation

Under the proposed policy reforms for the monograph, most innovations would occur through submission of an OMOR by an industry requestor. However, it is possible that a few types of changes could be accomplished through a process that would not require an OMOR for each change. One area where such changes might occur is for minor dosage form changes. In order to clarify which types of minor changes to solid oral dosage forms might be possible without an OMOR (when the monograph does not already specifically provide for these types of changes), FDA would issue an administrative order outlining key requirements and guidance providing details of what sponsors should do in order to comply with the administrative order. This order and guidance are referred to together as an “order/guidance pair”. Sponsors would need to have data on file, available at FDA request, to support the safety and efficacy of drugs with the minor change.

Timelines

Currently, it takes many years to make a change to a monograph, and the goal under monograph reform is to shorten that timeframe substantially, while still maintaining a public comment process between proposed and final orders, and maintaining FDA’s standards for safety and efficacy. For example, it took approximately seven years to amend a monograph to require new warnings for liver injury for acetaminophen and GI bleeding for nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. The Advisory Committee meeting was held September 19 and 20, 2002. The proposed rule was published December 26, 2006, and the final rule was published April 29, 2009. These warnings were very high priorities for the Agency to address urgent safety issues, yet it took that long. These substantially shortened timeframes are reflected in the tables in the Goals Letter, and would reduce what is currently a years-long process to between 17.5 and 23.5 months, with support from user fees (see Figure 3 below).

Figure 3

Communication and Transparency

FDA is committed to enhancing communication and transparency for the public and regulated industry. The Goals Letter details meeting management goals, which include timely responses to meeting requests, meeting scheduling, meeting background packages, preliminary responses to requestor questions, requestor notifications, anticipated agendas, meeting minutes, number of meetings per year, performance goals, and meetings guidance development, and a forecast of planned monograph activities.

Conclusion

FDA is committed to enhancing its core mission, which includes efforts to ensure and improve the safety and effectiveness of OTC Monograph drugs. Americans use OTC drugs every day, and these products will become increasingly important as patients take greater control of their own health. And yet the existing monograph system no longer functions well. We face significant challenges in completing monographs, addressing safety issues, and supporting innovation in the OTC marketplace. Reforms of the existing system are needed to promote innovation and choice for patients and consumers while also improving FDA’s ability to address urgent safety issues in a timely fashion and ensure the safety and effectiveness of OTC products. A wide range of stakeholders has come together to support these reforms and we hope to continue to work with Congress on legislation to make them a reality.