Vaccines for COVID-19: A Personal Reflection

By: Robert M. Califf, M.D., Commissioner of Food and Drugs

COVID-19—the disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 respiratory virus—has taken a terrible toll. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that COVID-19 is responsible for at least 1.2 million deaths in the U.S. and over 7 million deaths worldwide.1 Amid this catastrophic wave of death and remarkably severe illness, multiple emergency policies were enacted at every level of government and in private industry. In light of these impacts, we should engage in discussion and debate about those policies so that we can prepare effectively for the next pandemic. This essay is my personal reflection on the status of COVID vaccines, which constitute one of the most important elements of government policy, particularly as it relates to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and my term as Commissioner. It is not intended to be an exhaustive systematic review or to represent the policies of the current administration.

The System

In the context of a pandemic, FDA’s primary role regarding vaccine development is to work with manufacturers and the research community to ensure that scientific and ethical standards for product development, manufacturing, and clinical trial conduct are met, with the ultimate goal of producing safe and effective vaccines. When the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) determines that there is a public health emergency or a significant potential for a public health emergency, the Secretary may authorize FDA to issue Emergency Use Authorizations (EUAs) for medical countermeasures, including vaccines. When the FDA receives an EUA request, the FDA decides, generally after consultation with the independent Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee (VRBPAC), whether to grant an EUA based on an assessment of benefit and risk. The criteria for EUA include a scientific judgment by FDA that the known and potential benefits of a product outweigh its known and potential risks. This is a more flexible standard than the one applied in standard drug approval, which requires evidence from adequate, well-controlled clinical trials demonstrating that the benefits of the drug outweigh the risks. However, given that the COVID vaccines were developed for a broad population including healthy individuals, FDA determined that large randomized clinical trials, comparable to those required for the demonstration of vaccine effectiveness under a Biologics License Application (BLA), along with appropriate safety data, were needed to support the initial EUAs for the COVID vaccines.

Once FDA has authorized use of a vaccine, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), guided by its independent Advisory Committee for Immunization Practices (ACIP) for public health and clinical judgment, is responsible for recommending how to deploy it. The CDC considers factors including FDA review of vaccines in its recommendations and uses detailed analyses of benefit-risk tradeoffs, considering outcomes for potential vaccine recipients across the spectrum of risk.2 FDA’s subject matter experts and leaders from both agencies also serve as resources in ACIP meetings. The VRBPAC3 and ACIP4 proceedings are publicly available on the internet, including slides and extensive background documents from presentations.

COVID Vaccine Development

The United States’ response to the pandemic, Operation Warp Speed (OWS),5 led the world in developing COVID vaccines and medical countermeasures—in particular, leveraging mRNA technology to tailor vaccines to a particular strain of the relevant virus. Other countries, such as China and Russia, also developed vaccines without OWS involvement. The large, complex OWS collaboration across government, academia, and the medical products industry worked to create effective vaccines as rapidly as possible and was supported by decades of infrastructure-building in biomedical science, as well as significant (and ongoing) preparedness planning for pandemics by federal agencies, industry, and funded academic centers. Simultaneously, multiple manufacturers were also supported in using traditional vaccine development methods. Despite pressures that accompanied the rapid pace of development, FDA still required rigorous randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to support the initial EUAs for the COVID vaccines and provided vaccine developers with clear guidance on the data and information needed to support additional COVID vaccine EUAs.

Initial vaccine trials were focused on prevention of clinically evident disease. For the vaccines that were authorized, the efficacy criteria set by FDA prior to the completion of trials were surpassed by large margins,6,7 no major unexpected toxicities were encountered, and EUAs were granted quickly. Other vaccine candidates, however, were not developed beyond the investigational stage because they could not be reliably manufactured at scale, showed concerning safety signals in preclinical or clinical studies, or failed to demonstrate the required degree of efficacy. Although specific aspects of the OWS vaccine program could be debated, overall, it succeeded in developing effective vaccines without major safety signals in a very short time: less than 1 year, compared with an average of 8-10 years.8

Because the trajectory of the COVID pandemic was unknown and mutations that increased virulence or transmission of the virus subsequently occurred in unpredictable patterns, the approach to developing and recommending subsequent modifications to the authorized and approved vaccines was empirical. Decisions were based on data and information including the evolving epidemiology of the pandemic, small human trials, and detailed studies using immunological data to bridge to an assessment of efficacy. An important component of these efforts was the contribution of a global network of empirical epidemiologists, including networks comprising independent experts and faculty at major U.S. health systems and academic institutions,9 who evaluated toxicities and adverse outcomes and calculated vaccine efficacy and risks using standard methods that have been in place and refined through experience for decades.

The mRNA platforms used for two of the authorized COVID vaccines enabled rapid modification of the vaccines to match emerging variations in the virus. Given the public debate about the updated vaccines, now is a good time to consider the summary information from an enormous number of real-world clinical studies using modern methods of observational treatment comparisons, as well as population ecological studies conducted as vaccine updates were developed and deployed.

Clinical Outcome Data

The critical COVID-19 outcomes impacted by vaccination include symptomatic illness, serious illness, hospitalization, and death, as described in FDA guidance.10 Although overwhelming benefit for reducing the risk of symptomatic infection was seen in the initial clinical trials,6,7 as the virus evolved, this benefit was attenuated and became more modest. However, the reduction in symptomatic infection was partially restored with booster doses and updated vaccines.11,12

For all other key outcomes, at every level of analysis, vaccination substantially reduced risk and those who received updated vaccinations had fewer of these outcomes (death, hospitalization and long COVID) than those who did not receive the updated vaccination.13 For every recommended booster or updated vaccine, although the magnitude of benefit declined over time, a major benefit was observed over the course of the pandemic for prevention of death and hospitalization.14, 15, 16 A preliminary analyses by the Veterans Affairs Health System confirmed these benefits in the latest updated booster.17

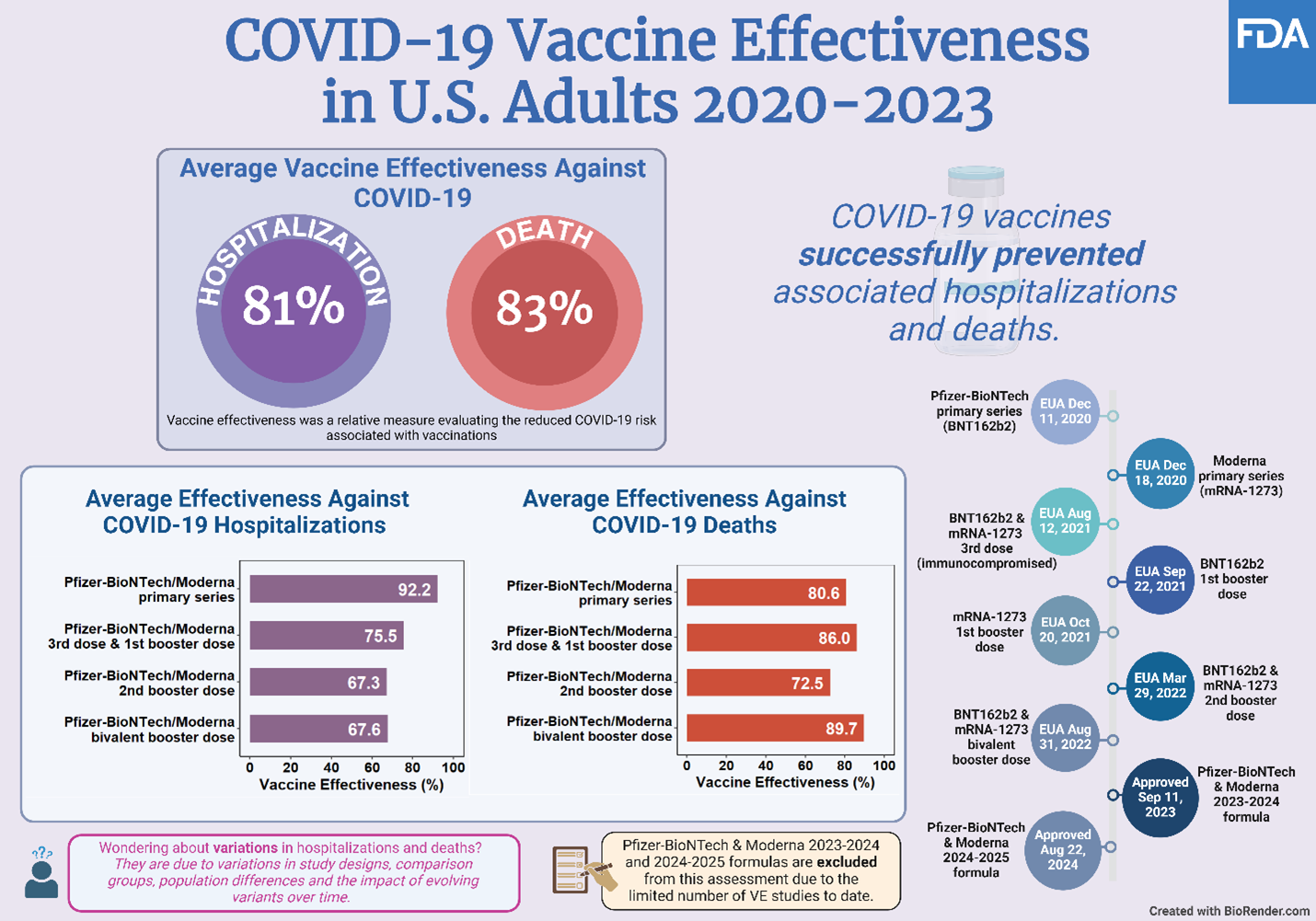

I asked the FDA Office of Biostatistics and Pharmacovigilance in CBER to update their view of the evidence to date (Figure 1). They found 19 high-quality studies of adults from the U.S. with various study populations, study designs, and comparison groups. These vaccine effectiveness studies did not measure the absolute reduced number of COVID-19 hospitalization or death, instead, they reported relative reduced risk. Their findings, while not meant to have the full force of a global systematic overview, confirmed the substantial benefit of vaccination and updated boosters throughout the sequence of initial vaccinations and booster updates. It should be noted that in order to include only studies that were mature and of high quality, data from the most recent full season were not included. These results confirm the many detailed analyses of benefits, risks and relevant populations over the entire period of vaccine deployment, which can be found on the VRBPAC3 and ACIP4 websites. Similar results in multiple studies have been reported from the U.S.,18,19 Europe,20 the U.K.,21 Israel,22 and Asia.23

An important point about these estimates is that the empirical estimate of vaccine effectiveness can vary based on the method used and whether the estimate is comparing an updated/booster dose with no vaccination, with a mix of vaccinated and unvaccinated people or with people who were up to date on primary vaccination and updates/boosters prior to update/boosters under evaluation. Although estimates vary, the vast majority of relevant large studies have shown significant reduction in death, hospitalization, and serious illness and a modest reduction in symptomatic illness. In particular, the most recent CDC estimates for effectiveness based on the 2023-2024 recommendations24 found a lower but still clinically important reduction in these outcomes.25 Thus, the estimates in Figure 1 are not meant to produce a specific estimate for current populations but rather to point out that since the initial approval and deployment of the vaccines, the heterogeneous network of government and independent epidemiologists have found consistent evidence of benefit for each of the updates and boosters in multiple evaluations over time.

Ecological analyses in multiple continents, countries,26 states,27 and counties28 also demonstrated that the higher the rate of vaccination and updated vaccination in the population, the lower the rates of COVID-related death, serious illness, and hospitalization. Maintaining an up-to-date status confers a further reduction in risk for both outcomes. The Commonwealth Fund has estimated that COVID vaccines saved 3.2 million lives and over 18 million hospitalizations in the first 2 years in the U.S. alone, as well as saving over $1TT.29

These benefits consistently declined within months after the initial vaccination or updated vaccination.30 Accordingly, the CDC recommends updated repeat vaccination (also known as “boosters” in much of the medical literature) using a version of the vaccine matched to currently circulating strains, particularly in high-risk persons characterized by older age, significant comorbidities (including obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease), and/or immune system compromise.31 The CDC’s detailed analysis of weighing the benefits and risks of updating the vaccine dose are publicly available in the ACIP Evidence to Recommendations for Use document.32 This same pattern has been observed with each updated vaccine/booster in multiple analyses from different datasets in every region of the world, leading the ACIP and CDC to recommend biannual updates/boosters for immunocompromised persons and those and patients over age 65;33 when this recommendation was finalized by the CDC.

Multiple analyses demonstrate a significant reduction in many other serious medical conditions in people who were vaccinated for COVID compared with those who were not, and for those who received sequential updated vaccines versus those who did not.34,35 Most notably, the incidence of major cardiovascular, neurological, and pulmonary disease events is lower in persons who were vaccinated and received the updates, compared with those who were never vaccinated or were initially vaccinated but did not receive vaccine updates.36

Importantly, when overall health outcomes have been evaluated, COVID vaccination stands out as protective, consistent with the protean manifestations of COVID infection across all organ systems.37, 38, 39 This issue of the cause of an individual event or group of clinical events has been a source of confusion with regard to COVID and vaccination. Because SARS-CoV-2 infection causes thrombogenicity, for example, one cannot determine in an individual case whether a sudden death, stroke, or myocardial infarction (or the absence of such an event) was a result of COVID-19, vaccination, or other factors. The only way to sort this issue is by comparing outcomes in people who were vaccinated with those who were not and to compare people with a COVID-19 infection with those without an infection. This common issue is the basis for FDA’s guidance on regulatory requirements for adverse event reporting in clinical trials and for postmarket adverse event reporting—the aggregate event rates as a function of intervention vs. comparator, not adjudication of individual events, enable the determination of cause and effect.40,41 The epidemiology in COVID-19 is overwhelming: it is associated with increased rates of adverse outcomes across multiple organ systems (vascular, heart, brain, lungs, etc.), and vaccinations reduce the rates of these events.42

Finally, the prevention and amelioration of “long COVID”43 has emerged as a major benefit of vaccination. This complex problem has affected millions of Americans, including many children, with well-documented and devastating consequences for quality of life. Analyses consistently show that vaccinated persons have a substantially lower rate of long COVID than unvaccinated people; further, those who received vaccine updates/boosters had lower rates of long COVID than did those who did not receive the updates.44,45 A recent publication emphasized this issue for essential workers—vaccination was associated with less recurrent infection and lower rates of long COVID.46 The absence of effective treatment for long COVID reinforces the importance of preventing it.

As with all vaccines, minor symptoms of temporary pain, swelling, and/or redness at the injection site, fatigue, headache, chills, muscle pain, and joint pain and fever are common. Serious allergic reactions are much less common. Anaphylaxis is rare but must be considered as a possibility when monitoring and caring for people immediately after vaccination. One uncommon toxicity of particular concern has been myocarditis and pericarditis, occurring most frequently in young men and requiring careful clinical care. However, to date, long-term outcomes appear favorable compared with other types of myocarditis and pericarditis.47 This safety signal emerged early in the deployment of the vaccines, particularly after a second dose. Importantly, across the age spectrum, the overall rate of cardiovascular events is lower in people who have been vaccinated compared with those who have not been vaccinated and lowest in people who have received the updated vaccine.48

The effectiveness of the vaccine safety surveillance program was demonstrated by the postmarket evaluation of the Johnson & Johnson coronavirus vaccine, which was developed using a vaccine technology that had previously been explored in a variety of infectious disease settings and showed beneficial effects on symptomatic disease in initial COVID-19 studies. Unfortunately, global surveillance revealed a rare but excess rate of life-threatening clotting as part of the thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) syndrome, leading to limitations on its scope of authorization before the authorization was eventually revoked in May of 2023,49 given the availability of alternatives that did not carry this risk. The sensitivity of surveillance was demonstrated by the finding that only 60 of 18 million people receiving the vaccine developed TTP.

An additional adjuvanted protein-based vaccine produced by Novavax met the criteria for EUA and its evaluation has produced positive data similar to the mRNA vaccines.50 Although uptake has been low compared with the mRNA vaccines, its safety and effectiveness has been sufficiently supported by the data and information submitted to FDA.

Populations Where Intense Debate Has Occurred

Although the evidence that the benefit of vaccination for COVID outweighs the risks is overwhelmingly clear in high-risk populations, considerable skepticism has been expressed about the benefit-risk calculation in children, teenagers,51 healthy non-elderly adults, pregnant women, and people with previous COVID infection. While acknowledging the limitations of subgroup analysis, there is good reason to ascertain whether a favorable benefit-risk balance is limited to high-risk populations.

Across these subgroups, the relative reduction in serious events (death, hospitalization, and long COVID) is similar. This is because, as in most medical interventions,52 in populations with lower underlying risk, the absolute number of events prevented is less, meaning that more people need to be vaccinated to prevent an event in these lower-risk populations. Although the magnitude of benefit is less in these lower-risk populations, detailed analyses of available literature presented at ACIP meetings continue to show that estimated benefits in all of these various populations outweigh estimated risks. Detailed analyses of the multiple networks of health systems that monitor vaccine effectiveness in their patient populations make this point clearly.53, 54, 55, 56

These findings are particularly strong and important for pregnant women.57, 58, 59 In people who are at low risk of death and hospitalization from COVID, although the absolute magnitude of benefit is small, the relative reduction in risk is consistent with the overall results. This is also the observation in children,60 adolescents,61 and young adults.62 Depending on the size of the study and the underlying risk of the population, many studies focus on hospitalization, an easily measurable and reliable outcome measure, whereas impact on mortality is generally observed in higher risk populations and larger studies.

Another important issue is the role of previous infection. Although most people initially infected with SARS-CoV-2 have an immune response that protects partially against recurrent infection and serious illness, there is also a higher risk of severe illness and long COVID in persons with subsequent infections.63 Vaccination also further reduced the risk of symptomatic reinfection64 as well as severe illness and hospitalization63 in people with prior infection, a beneficial effect that was observed with initial vaccination and with subsequent vaccinations. Thus, while prior infection is somewhat protective, vaccination is important to minimize risk in this population also.

The Future

The vast majority of the U.S. population has some level of immunity from the combined impact of infection and immunization. However, the evolving virus continues to cause serious illness and death globally, and in the U.S., COVID remained in the top 10 causes of death in 2023. It will remain a major cause of death in 2024, although likely dropping out of the top 10. After a recent lull in viral activity, we are experiencing a resurgence, which in tandem with the upswing in influenza and respiratory syncytial virus, in addition to the threat of H5N1 transmission, could portend a risky winter. The low uptake of updated booster vaccination this year,65 which can be followed weekly on the CDC dashboard, likely will leave many people vulnerable. For this reason, it is incumbent upon clinicians to recommend updated annual vaccination and add to the evidence to date.

However, the low uptake also presents a chance to fortify the evidence. From the perspective of the quality of evidence, after the initial high-quality RCTs that were focused on symptomatic disease, all subsequent comparisons are based on a mix of large, observational treatment comparisons and randomized trials for specific subpopulations, updated vaccines, and assessment of immunological response. Although these types of analyses are always subject to methodological questions, the consistency of observations in every region of the world by multiple independent governments and investigators makes a compelling case that benefits outweigh risks in every category, with rare exceptions of people with a history of severe allergic reactions to components of the vaccines. These methods have been used for decades and have successfully identified toxicities of vaccines. Nevertheless, given that the majority of Americans are choosing not to receive the updated vaccines or boosters and many clinicians are not pressing the issue, the conditions of equipoise may be in effect for significant segments of the population. Conducting one or more large RCTs comparing the next proposed update with placebo would provide an important addition to the body of evidence, including an updated benefit-risk calculation and specific information about populations that have been the source of most intense skepticism.

Going forward, there is also ample reason to focus on the clinical epidemiology of vaccine-associated adverse outcomes to sort out when the events are caused by the vaccine versus events that would have occurred anyway, to better understand risk factors for these events and to devise effective interventions. Similar continued focus on long COVID is also essential because of the enormous toll it is taking across the age spectrum.

In my career as a cardiologist, once it was proven that reperfusion substantially reduced mortality in patients with ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction despite the risk of intracranial hemorrhage, it became a standard of care, and every individual who died without the opportunity for benefit was a tragedy. Just as with coronary reperfusion, COVID vaccination is not 100% effective and serious toxicity or death, though exceedingly rare, can be caused by the intervention. However, when facing the decisions prospectively, my opinion, which is fully consistent with that of the FDA and CDC, is that it is clear that the benefits substantially outweigh the risks. The question for the individual is: “If I take the vaccine, will I be more likely to be alive, free of serious illness, hospitalization, and long COVID than if I do not?” Based on our most current knowledge, I believe the answer is clearly “yes.” I hope that as a society we can enhance the degree to which practice is consistent with best evidence and continue to develop better clinical evidence to inform changes in policy and individual patient recommendations in the future.

References

- World Health Organization Data. WHO COVID-19 Dashboard. Number of COVID-19 deaths reported to WHO (total cumulative). Accessed December 16, 2024. https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/deaths

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Evidence to Recommendations Frameworks. September 3, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/acip/evidence-to-recommendations/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/recs/grade/etr.html

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Meeting materials. Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee. https://www.fda.gov/advisory-committees/vaccines-and-related-biological-products-advisory-committee/meeting-materials-vaccines-and-related-biological-products-advisory-committee

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. ACIP Meeting Information. https://www.cdc.gov/acip/meetings/index.html

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Operation Warp Speed: Vaccines, Diagnostics, and Therapeutics. Testimony: Senate Appropriations Subcommittee on Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies. July 2, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/washington/testimony/2020/t20200702.htm

- Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, et al.; C4591001 Clinical Trial Group. Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(27):2603-2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577. PMID: 33301246; PMCID: PMC7745181.

- Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, et al.; COVE Study Group. Efficacy and Safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(5):403-416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2035389. PMID: 33378609; PMCID: PMC7787219.

- Puthumana J, Egilman AC, Zhang AD, Schwartz JL, Ross JS. Speed, Evidence, and Safety Characteristics of Vaccine Approvals by the US Food and Drug Administration. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(4):559–560. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.7472. PMID: 33170923; PMCID: PMC7656319.

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccine Effectiveness Studies. July 12, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/covid/php/surveillance/vaccine-effectiveness-studies.html

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Development and Licensure of Vaccines to Prevent COVID-19. Guidance for Industry. October 2023. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/development-and-licensure-vaccines-prevent-covid-19

- Gupta RK, Topol EJ. COVID-19 vaccine breakthrough infections. Science. 2021;374(6575):1561–1562. doi: 10.1126/science.abl8487. PMID: 34941414.

- Menni C, May A, Polidori L, et al. COVID-19 vaccine waning and effectiveness and side-effects of boosters: a prospective community study from the ZOE COVID Study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022 Jul;22(7):1002-1010. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00146-3. PMID: 35405090; PMCID: PMC8993156.

- Johnson AG, Linde L, Ali AR, et al. COVID-19 Incidence and Mortality Among Unvaccinated and Vaccinated Persons Aged ≥12 Years by Receipt of Bivalent Booster Doses and Time Since Vaccination - 24 U.S. Jurisdictions, October 3, 2021-December 24, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(6):145–152. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7206a3. PMID: 36757865; PMCID: PMC9925136.

- Sukik L, Chemaitelly H, Ayoub HH, et al. Effectiveness of two and three doses of COVID-19 mRNA vaccines against infection, symptoms, and severity in the pre-omicron era: A time-dependent gradient. Vaccine. 2024;42(14):3307–3320. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2024.04.026. PMID: 38616439.

- Link-Gelles R, Ciesla AA, Mak J, et al. Early Estimates of Updated 2023-2024 (Monovalent XBB.1.5) COVID-19 Vaccine Effectiveness Against Symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infection Attributable to Co-Circulating Omicron Variants Among Immunocompetent Adults - Increasing Community Access to Testing Program, United States, September 2023-January 2024. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2024;73(4):77–83. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7304a2. PMID: 38300853; PMCID: PMC10843065.

- Bobrovitz N, Ware H, Ma X, et al. Protective effectiveness of previous SARS-CoV-2 infection and hybrid immunity against the omicron variant and severe disease: a systematic review and meta-regression. Lancet Infect Dis. 2023;23(5):556–567. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00801-5. PMID: 36681084; PMCID: PMC10014083.

- Appaneal HJ, Lopes VV, Puzniak L, et al. Early effectiveness of the BNT162b2 KP.2 vaccine against COVID-19 in the US Veterans Affairs Healthcare System [preprint]. medRxiv 2024.12.26.24319566; doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.12.26.24319566

- Caffrey AR, Appaneal HJ, Lopes VV, et al. Effectiveness of BNT162b2 XBB vaccine in the US Veterans Affairs Healthcare System. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):9490. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-53842-w. PMID: 39488521; PMCID: PMC11531596.

- Ma KC, Surie D, Lauring AS, et al. Effectiveness of Updated 2023-2024 (Monovalent XBB.1.5) COVID-19 Vaccination Against SARS-CoV-2 Omicron XBB and BA.2.86/JN.1 Lineage Hospitalization and a Comparison of Clinical Severity-IVY Network, 26 Hospitals, October 18, 2023-March 9, 2024. Clin Infect Dis. 2024:ciae405. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciae405. PMID: 39107255.

- Iacobucci G. Covid-19: Vaccines have saved at least 1.4 million lives in Europe, WHO reports. BMJ. 2024;384:q125. doi: 10.1136/bmj.q125. PMID: 38233071.

- U.K. Health Security Agency. COVID 19 Vaccine Surveillance Report. November 2024. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/6735ddce0b168c11ea8230f2/Vaccine_surveillance_report_2024_week_46.pdf

- Muhsen K, Cohen D. COVID-19 vaccination in Israel. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27(11):1570–1574. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.07.041. PMID: 34384875; PMCID: PMC8351306.

- Tan CY, Chiew CJ, Pang D, et al. Effectiveness of bivalent mRNA vaccines against medically attended symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19-related hospital admission among SARS-CoV-2-naive and previously infected individuals: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2023 Dec;23(12):1343–1348. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(23)00373-0. PMID: 37543042.

- Panagiotakopoulos L, Moulia DL, Godfrey M, et al. Use of COVID-19 Vaccines for Persons Aged ≥6 Months: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices - United States, 2024-2025. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2024;73(37):819-824. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7337e2. PMID: 39298394; PMCID: PMC11412444.

- Roper LE, Godfrey M, Link-Gelles R, et al. Use of Additional Doses of 2024–2025 COVID-19 Vaccine for Adults Aged ≥65 Years and Persons Aged ≥6 Months with Moderate or Severe Immunocompromise: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices — United States, 2024. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2024;73:1118–1123. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7349a2

- Hoxha I, Agahi R, Bimbashi A, et al. Higher COVID-19 Vaccination Rates Are Associated with Lower COVID-19 Mortality: A Global Analysis. Vaccines (Basel). 2022;11(1):74. doi: 10.3390/vaccines11010074. PMID: 36679919; PMCID: PMC9862920.

- Du H, Saiyed S, Gardner LM. Association between vaccination rates and COVID-19 health outcomes in the United States: a population-level statistical analysis. BMC Public Health. 2024;24(1):220. doi: 10.1186/s12889-024-17790-w. PMID: 38238709; PMCID: PMC10797940.

- McLaughlin JM, Khan F, Pugh S, Swerdlow DL, Jodar L. County-level vaccination coverage and rates of COVID-19 cases and deaths in the United States: An ecological analysis. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2022;9:100191. doi: 10.1016/j.lana.2022.100191. PMID: 35128511; PMCID: PMC8802692.

- The Commonwealth Fund. Two Years of U.S. COVID-19 Vaccines Have Prevented Millions of Hospitalizations and Deaths. Accessed December 31, 2024. Available at: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2022/two-years-covid-vaccines-prevented-millions-deaths-hospitalizations

- Feikin DR, Higdon MM, Abu-Raddad LJ, et al. Duration of effectiveness of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 disease: results of a systematic review and meta-regression. Lancet. 2022;399(10328):924-944. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00152-0. Erratum in: Lancet. 2024 Aug 31;404(10455):e3. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00428-7. Erratum in: Lancet. 2023 Feb 25;401(10377):644. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00331-8. PMID: 35202601; PMCID: PMC8863502.

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Staying up to date with COVID-19 vaccines. October 4, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/covid/vaccines/stay-up-to-date.html

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. ACIP Evidence to Recommendations (EtR) for Use of 2024-2025 COVID-19 Vaccines in Persons ≥6 Months of Age. September 13, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/acip/evidence-to-recommendations/covid-19-2024-2025-6-months-and-older-etr.html

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Recommends Second Dose of 2024-2025 COVID-19 Vaccine for People 65 Years and Older and for People Who Are Moderately or Severely Immunocompromised. October 23, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2024/s1023-covid-19-vaccine.html

- Lam ICH, Zhang R, Man KKC, et al. Persistence in risk and effect of COVID-19 vaccination on long-term health consequences after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):1716. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-45953-1. PMID: 38403654; PMCID: PMC10894867.

- Xie Y, Choi T, Al-Aly Z. Postacute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection in the Pre-Delta, Delta, and Omicron Eras. N Engl J Med. 2024;391(6):515-525. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2403211. PMID: 39018527; PMCID: PMC11687648.

- Català M, Mercadé-Besora N, Kolde R, Trinh NTH, Roel E, Burn E, Rathod-Mistry T, Kostka K, Man WY, Delmestri A, Nordeng HME, Uusküla A, Duarte-Salles T, Prieto-Alhambra D, Jödicke AM. The effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines to prevent long COVID symptoms: staggered cohort study of data from the UK, Spain, and Estonia. Lancet Respir Med. 2024 Mar;12(3):225-236. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(23)00414-9. PMID: 38219763.

- Cai M, Xie Y, Topol EJ, Al-Aly Z. Three-year outcomes of post-acute sequelae of COVID-19. Nat Med. 2024;30(6):1564-1573. doi: 10.1038/s41591-024-02987-8. PMID: 38816608; PMCID: PMC11186764.

- Al-Aly Z, Xie Y, Bowe B. High-dimensional characterization of post-acute sequelae of COVID-19. Nature. 2021;594(7862):259-264. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03553-9. PMID: 33887749.

- Xie Y, Xu E, Al-Aly Z. Risks of mental health outcomes in people with covid-19: cohort study. BMJ. 2022;376:e068993. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2021-068993. PMID: 35172971; PMCID: PMC8847881.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. IND Application Reporting: Safety Reports. October 19, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/investigational-new-drug-ind-application/ind-application-reporting-safety-reports

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Postmarketing Adverse Event Reporting Compliance Program. May 5, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/surveillance/postmarketing-adverse-event-reporting-compliance-program

- Boyce TG, McClure DL, Hanson KE, et al. Lack of Evidence for Vaccine-Associated Enhanced Disease From COVID-19 Vaccines Among Adults in the Vaccine Safety Datalink. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2024;33(8):e5863. doi: 10.1002/pds.5863. PMID: 39155049; PMCID: PMC11377022.

- Davis HE, McCorkell L, Vogel JM, Topol EJ. Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms and recommendations. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2023;21(3):133–146. doi: 10.1038/s41579-022-00846-2. Erratum in: Nat Rev Microbiol. 2023 Jun;21(6):408. doi: 10.1038/s41579-023-00896-0. PMID: 36639608; PMCID: PMC9839201.

- Byambasuren O, Stehlik P, Clark J, Alcorn K, Glasziou P. Effect of COVID-19 vaccination on long COVID: systematic review. BMJ Med. 2023;2(1):e000385. doi: 10.1136/bmjmed-2022-000385. PMID: 36936268; PMCID: PMC9978692.

- Watanabe A, Iwagami M, Yasuhara J, Takagi H, Kuno T. Protective effect of COVID-19 vaccination against long COVID syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccine. 2023;41(11):1783-1790. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2023.02.008. PMID: 36774332; PMCID: PMC9905096.

- Babalola TK, Clouston SAP, Sekendiz Z, et al. SARS-COV-2 re-infection and incidence of post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) among essential workers in New York: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2025. DOI: 10.1016/j.lana.2024.100984

- Semenzato L, Le Vu S, Botton J, et al. Long-term prognosis of patients with myocarditis attributed to COVID-19 mRNA vaccination, SARS-CoV-2 infection, or conventional etiologies. JAMA. 2024;332(16):1367–1377. doi: 10.1001/jama.2024.16380. PMID: 39186694; PMCID: PMC11348078.

- Xu Y, Li H, Santosa A, et al. Cardiovascular events following coronavirus disease 2019 vaccination in adults: a nationwide Swedish study. Eur Heart J. 2024:ehae639. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehae639. PMID: 39344920; PMCID: PMC11704415.

- Oliver SE, Wallace M, See I, et al. Use of the Janssen (Johnson & Johnson) COVID-19 Vaccine: Updated Interim Recommendations from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices - United States, December 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(3):90-95. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7103a4. PMID: 35051137; PMCID: PMC8774160.

- Áñez G, Dunkle LM, Gay CL, et al. Safety, Immunogenicity, and Efficacy of the NVX-CoV2373 COVID-19 Vaccine in Adolescents: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(4):e239135. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.9135. PMID: 37099299; PMCID: PMC10536880.

- Almendares OM, Ruffin JD, Collingwood AH, et al. Previous Infection and Effectiveness of COVID-19 Vaccination in Middle- and High-School Students. Pediatrics. 2023;152(6):e2023062422. doi: 10.1542/peds.2023-062422. PMID: 37960897; PMCID: PMC11247457.

- Califf RM, DeMets DL. Principles from clinical trials relevant to clinical practice: Part I. Circulation. 2002;106(8):1015-21. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000023260.78078.bb. PMID: 12186809.

- DeCuir J, Payne AB, Self WH, et al; CDC COVID-19 Vaccine Effectiveness Collaborators. Interim Effectiveness of Updated 2023-2024 (Monovalent XBB.1.5) COVID-19 Vaccines Against COVID-19-Associated Emergency Department and Urgent Care Encounters and Hospitalization Among Immunocompetent Adults Aged ≥18 Years - VISION and IVY Networks, September 2023-January 2024. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2024;73(8):180-188. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7308a5. PMID: 38421945; PMCID: PMC10907041.

- Klein NP, Demarco M, Fleming-Dutra KE, et al. Effectiveness of BNT162b2 COVID-19 Vaccination in Children and Adolescents. Pediatrics. 2023;151(5):e2022060894. doi: 10.1542/peds.2022-060894. PMID: 37026401

- Tartof SY, Slezak JM, Frankland TB, et al. Estimated Effectiveness of the BNT162b2 XBB Vaccine Against COVID-19. JAMA Intern Med. 2024;184(8):932–940.

- Tartof SY, Slezak JM, Puzniak L, et al. Effectiveness of BNT162b2 BA.4/5 bivalent mRNA vaccine against a range of COVID-19 outcomes in a large health system in the USA: a test-negative case-control study. Lancet Respir Med. 2023;11(12):1089–1100. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(23)00306-5. Erratum in: Lancet Respir Med. 2023 Dec;11(12):e98. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(23)00422-8. PMID: 37898148.

- Rahmati M, Yon DK, Lee SW, Butler L, Koyanagi A, Jacob L, Shin JI, Smith L. Effects of COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy on SARS-CoV-2 infection and maternal and neonatal outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Med Virol. 2023;33(3):e2434. doi: 10.1002/rmv.2434. PMID: 36896895.

- Avrich Ciesla A, Lazariu V, Dascomb K, et al. Effectiveness of the Original Monovalent and Bivalent COVID-19 Vaccines Against COVID-19-Associated Emergency Department and Urgent Care Encounters in Pregnant Persons Who Were Not Immunocompromised: VISION Network, June 2022-August 2023. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2024;11(9):ofae481. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofae481. PMID: 39286032; PMCID: PMC11403472.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. COVID-19 Vaccines and Pregnancy: Conversation Guide: Key Recommendations and Messaging for Clinicians. Accessed January 11, 2025. https://www.acog.org/covid-19/covid-19-vaccines-and-pregnancy-conversation-guide-for-clinicians

- Kitano T, Salmon DA, Dudley MZ, Thompson DA, Engineer L. Benefit-Risk Assessment of mRNA COVID-19 Vaccines in Children Aged 6 Months to 4 Years in the Omicron Era. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2024;13(2):129-135. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piae002. PMID: 38236136.

- Wu Q, Tong J, Zhang B, et al. Real-World Effectiveness of BNT162b2 Against Infection and Severe Diseases in Children and Adolescents. Ann Intern Med. 2024;177(2):165-176. doi: 10.7326/M23-1754. PMID: 38190711.

- Funk PR, Yogurtcu ON, Forshee RA, Anderson SA, Marks PW, Yang H. Benefit-risk assessment of COVID-19 vaccine, mRNA (Comirnaty) for age 16-29 years. Vaccine. 2022;40(19):2781-2789. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.03.030. PMID: 35370016; PMCID: PMC8958165.

- Bowe B, Xie Y, Al-Aly Z. Acute and postacute sequelae associated with SARS-CoV-2 reinfection. Nat Med. 2022;28(11):2398–2405. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-02051-3. PMID: 36357676; PMCID: PMC9671810.

- Mongin D, Bürgisser N, Laurie G, Schimmel G, Vu DL, Cullati S; Covid-SMC Study Group; Courvoisier DS. Effect of SARS-CoV-2 prior infection and mRNA vaccination on contagiousness and susceptibility to infection. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):5452. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-41109-9. PMID: 37673865; PMCID: PMC10482859.

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Weekly COVID-19 Vaccination Dashboard. January 8, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/covidvaxview/weekly-dashboard/

Figure 1. COVID-19 Vaccine Effectiveness in U.S. Adults, 2020-2023